Writer / Dan Wakefield

I doubt there is a human being who does not at some later time wish we had said something that we didn’t. I’m not talking about the common fantasies of telling off a former friend or enemy, striking them with our rapier wit that would have cut them down to size after they dared offend us. Those things rarely work satisfactorily, and I can only think of one instance when a much later put-down gave justified satisfaction to the wielder of the word of revenge.

Kurt Vonnegut was humiliated as a senior at Shortridge High School during a custom that allowed faculty members to give “joke presents” to some of the seniors (the ritual was happily discontinued by the time I got to Shortridge.) The football coach had given Kurt, self-described as “an awkward, gangly kid,” a subscription to The Charles Atlas Body Building Course. The teenager felt humiliated in front of his classmates and faculty.

Several decades later, while sipping bourbon by himself in his New York apartment, feeling satisfied as only a writer does after his novel (“Slaughterhouse Five”) is hailed on the front page of The New York Times and becomes an international best-seller, Kurt picked up the phone and asked for the number of that football coach who was still alive. He got him on the line and said simply “This is Kurt Vonnegut, and I doubt if you remember me, but I wanted to tell you my body turned out just fine.”

‘Nuff said.

Few of us can think of the right thing to say on the spot – it took Vonnegut more than 20 years and the confidence of a best-seller to find a great response. Mostly we sputter a curse or two and afterward feel worse than we did before attempting our verbal counter-attack.

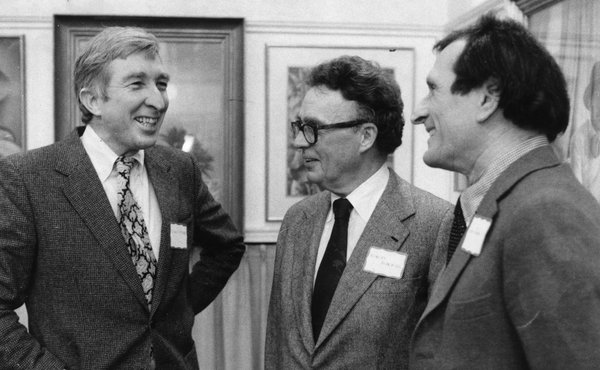

On the higher ground of a wish to acknowledge someone, to give a friend or colleague a deserved compliment, we often hold back, wishing later we had said it. One of my missed opportunities occurred when I was sitting on the stage of Clowes Hall with Vonnegut and John Updike in the first “Spirit and Place” event. Updike was saying that many English writers could be counted on to publish a first-class new book every year or so, year after year, but we don’t have any writers like that in America today.

“But we do, John – it’s you!”

That sentence was in my head, but it didn’t come out of my mouth. I truly admired the regularity with which Updike managed to publish a new novel just about every year and a half, and in between the novels, he often came out with a collection of assorted prose or poetry, all of it high quality work.

I hesitated to say it – I don’t know why – maybe fearing I would sound as if I were currying favor or showing off my own professional generosity, but the fact is I did and still do believe he was as good as he was prolific and one of the few American writers of his time to exhibit such qualities.

I wish I had said it, but now it’s too late to tell him. I doubt if it would have made his evening, but it always helps to feel recognized and acknowledged, and it helps the person who recognizes and acknowledges to know that he or she has expressed a heartfelt opinion.

I wish I had said it, but now it’s too late to tell him. I doubt if it would have made his evening, but it always helps to feel recognized and acknowledged, and it helps the person who recognizes and acknowledges to know that he or she has expressed a heartfelt opinion.

Such dilemmas do not apply only to writers! I wish like the devil I could have opened up and said what I felt to a man who came to a book signing I gave at a Barnes and Noble here in Indy back in the ‘80s. One of my old School #80 classmates came to my reading, and I asked him to have coffee afterwards. He had not only been a classmate, but he had played basketball at my backyard backboard on Winthrop – a breeding ground of future Broad Ripple High School stars!

When I met him years later at that book event, Dick “Itchy” Richardson had become a successful contractor, and he seemed very subdued and quiet. He looked the same – tall, dark-haired, loose-limbed, handsome – but I had the desire to shake him and say, “Hey, Dick – Itchy – you were a great kid! You could make me laugh with your loosey-goosey style, you could send our outdoor basketball games into hysteria when you urged people not to just ‘flick’ – to shoot too much – but to ‘fo-leek,’ which meant to really shoot way too much and do it with no shame, to throw up impossible baskets with glee.” But we both just sat there over our coffee like dodos or department store dummies, being polite, restrained and ‘grown-up.’

When I moved back to Indy four years ago, I asked if you [Dick] were around, knowing this time I would thank you for giving me so much fun and hope I could get your comic spirit going again. I wanted to enjoy the deep-down pleasure of happy hysteria that some people have the gift of passing on to others. I’d shake you until you smiled and the laughs came rolling out, and I could join you in the kind of hysterics that made us fall to the ground. But you had already gone, I was told, and not just left the city but left this life, taking your laughs with you. I had missed my chance to say thanks for lighting and lightening my early life.

At my age, so many people are passing from my chance to thank them that I try to make a point of doing it, especially with people I am no longer able to see very often. When I last visited Boston, I made a point of looking up a man to whom I owed a great deal. I met Robert Manning when I was on a Nieman Fellowship in Journalism at Harvard, and he was editor of The Atlantic Monthly. I wrote a piece he liked and published, and when I ended up living in Boston after the Nieman year, we saw a good deal of one another.

I wrote in a fairly regular way for the magazine, and he made me a Contributing Editor (the title had no salary but gave me the use of a beautiful office overlooking The Boston Public Garden.) One evening in the spring of 1967, Manning was cooking steaks on the grill in the yard of his house in Cambridge, and we both were sipping dry martinis. He spoke of how difficult it was for a monthly magazine to cover the rapidly changing events in the Vietnam war.

“Maybe what we should do,” he mused, “is to send someone around this country to see how the war is affecting us.”

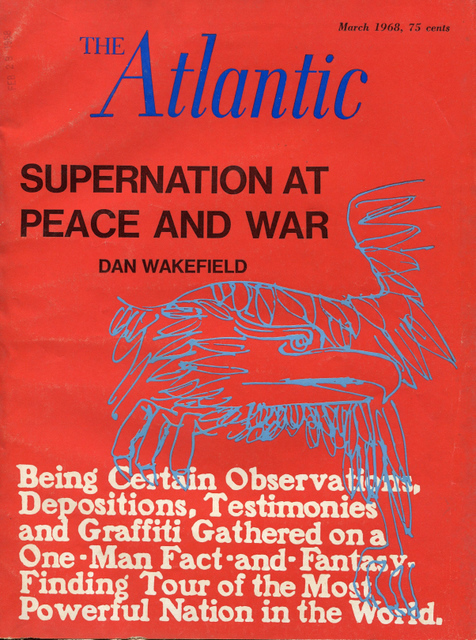

I agreed that was a good idea, and through the charcoal haze of the grilling steaks and the silver sting of the martinis, he asked if I would like to take on that assignment. I didn’t hesitate to say yes. For six months, I traveled throughout the country, talking with all kinds of people about the war. I ended my travels in Washington, D.C., to interview people in government and write what became an entire issue of The Atlantic in March 1968, called “Supernation at Peace and War,” which then was published as a book.

I agreed that was a good idea, and through the charcoal haze of the grilling steaks and the silver sting of the martinis, he asked if I would like to take on that assignment. I didn’t hesitate to say yes. For six months, I traveled throughout the country, talking with all kinds of people about the war. I ended my travels in Washington, D.C., to interview people in government and write what became an entire issue of The Atlantic in March 1968, called “Supernation at Peace and War,” which then was published as a book.

Manning essentially had trusted me with his magazine and his reputation as an editor. The Atlantic had never before devoted a whole issue to a single article and author – a 36-year-old version of me. And I didn’t fail the trust. That issue of the magazine sold out our rival Harpers, and their whole issue was given over to Norman Mailer’s “The Steps of The Pentagon,” later published in book form as “The Armies of the Night.”

When I went to Boston several years ago, Bob had retired with his wife to Cape Cod, but he sometimes came in to spend a few days in their condo in the city. It was there I asked him to lunch. Afterward, we went to his home in Boston’s South End and talked of the old days. After we had reminisced for an hour or so, he asked “Have we covered everything?”

I said, “No, but there’s one thing left.” “Oh? What’s that?”

he asked. “I want to thank you,” I said, “for being good to me.”

When you’re young, you think that every opportunity someone gives you is your just due. You later realize it’s because someone has put their faith in you and risked their own reputation to bet on your chance of coming through for them. I wish I could shake the hand of each one who has blessed me in that way, but many are gone. At least I am glad that I said what I wanted and needed to say to Bob Manning, one of the mentors who took a chance on me and who I lived to appreciate and express my thanks.