Getting Familiar With the Burrows Built by Animals Just Beneath Our Feet

Writer / Erin Kinnetz

Photography Provided

“Ew, is that a snake hole?” A shiver of excitement and unease passes through the second-graders experiencing their first hike at the Parklands of Floyds Fork. It is, of course, not a snake hole. Our tough, clay-heavy soil is not easy for an animal with no arms or legs to dig. None of our burrows belong to snakes even though they might slither inside looking for a meal from time to time.

Holes and burrows ignite our imagination. They are a clear sign of activity in the forests, meadows and stream banks. All sorts of mysterious, cute animal activities may be happening below our feet. Let me introduce you to some of the most common burrows in our native area. First, some vocabulary:

Burrows: Underground tunnels and rooms. They may be large or small, and they may have many rooms and tunnels or only one.

Fossorial: Describes an animal that is skilled at digging, burrowing and living underground.

We’ll start in the meadows and forest floor with a gregarious animal that is a whiz at elaborate underground homes – the groundhog. These large ground squirrels can make a series of tunnels and chambers that can add up to 65 feet of tunnel footage. Groundhogs are good at keeping things orderly in their well-patrolled tunnels. They will have separate chambers for their bedroom, a pantry of stored vegetables, a latrine, a nursery and at least two exits. Groundhogs are also known to build themselves a summer home and a winter home. Unlike their prairie-dog cousins, groundhogs are solitary. That’s one extensive network per single groundhog, but they may not be the only ones living there. In the winter, they will construct elaborate, maze-like tunnels with trap doors and dead ends to confuse predators that might be coming for them during hibernation. This leaves a lot of room for other animals looking for a winter resting place. Box turtles, cottontails, snakes and even skunks are all known to squat in an empty chamber in a groundhog’s winter burrow.

This hole carries the highest risk for injury or getting a lawnmower wheel stuck, as it is typically eight to 12 inches in diameter. Groundhogs are a truly fossorial species, as they excavate all the dirt and carry it away from the entrance. Since they like to have multiple entrances and exits, they often display them in different ways. This means you may spot an entrance with a crescent-shaped mound of dirt surrounding it. This is like the grand entrance to their manor. Nearby may be a tidy hole that is flush with the ground, or partly obscured next to a stump or pile of rocks. They don’t want you to notice this one as much, as it is their private entrance. Beware, because these tricky animals sometimes construct an exit and then carefully sweep sticks and leaves loosely on top of it. This is their escape hatch in case of an emergency (truly an ankle-turner of a hole). While these animals may exasperate gardeners across eastern North America, they are incredibly important to our forests and meadows. Their burrowing aerates soil, allowing water to seep deeply into the soil, and helps with nutrient cycling. Many terrestrial animals would go homeless without these burrows as they rely on abandoned groundhog tunnels for their own starter homes.

The next earth mover we will look at is the mighty mole. This shy animal rarely comes above ground, but makes its presence well-known by digging up to 160 feet of tunnels per night! You’ll recognize this animal by their volcano-shaped mounds. There may not be a clear hole in the center of that mound since it may be covered in loose dirt. The long claws on their webbed, paddle-like front paws shred soil for easy movement. These animals essentially swim through the dirt. These molehills extend up to 40 inches below ground to their main living tunnels.

The shallow tunnels we commonly see in our yards and in the forest are feeding tunnels – three-inch-wide pathways of pushed-up dirt. Moles will only use these tunnels a couple of times before abandoning them. These nearly blind, cylindrically shaped animals are voracious insectivores. Moles will dig their tunnels, wait and feel for vibrations, and smell for wormy scents. They come back through their tunnels at top speed and gleefully gobble up all the worms and bugs that fall into their tunnel traps. Don’t worry about the plight of the mole if you step on and collapse one of these tunnels. Most likely the tunnel has already been abandoned by the mole and it has plans to construct a new feeding tunnel the next night. As annoying as landscapers may find these tunnels, moles are important predators that control our bug population and should be respected.

The shallow tunnels we commonly see in our yards and in the forest are feeding tunnels – three-inch-wide pathways of pushed-up dirt. Moles will only use these tunnels a couple of times before abandoning them. These nearly blind, cylindrically shaped animals are voracious insectivores. Moles will dig their tunnels, wait and feel for vibrations, and smell for wormy scents. They come back through their tunnels at top speed and gleefully gobble up all the worms and bugs that fall into their tunnel traps. Don’t worry about the plight of the mole if you step on and collapse one of these tunnels. Most likely the tunnel has already been abandoned by the mole and it has plans to construct a new feeding tunnel the next night. As annoying as landscapers may find these tunnels, moles are important predators that control our bug population and should be respected.

A chipmunk hole is a little harder to spot. While they make a multi-chamber home underground, they don’t make as much of a show about it as groundhogs or moles. These clever little ground squirrels like to place their tidy entrances disguised as a pile of rocks, a knot of roots, or a hole at the base of a tree. Using features of the forest, they will dig from their already constructed entrance. If you observe closely, you may see a hole that is two to three inches in diameter just below the roots or rocks. Like groundhogs, they will make several entrances and exits, some flush with the ground and others plugged up as escape hatches.

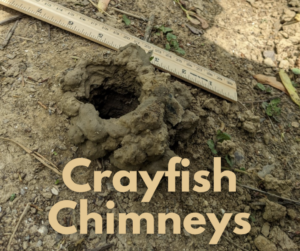

Not all animals like to keep their burrow dry. Some animals burrow below the water table to make it to water. As you explore the banks of Floyds Fork, you may notice what look like carefully constructed pots made of rounded balls of clay on either side of the stream. If you examine them a little more closely, you’ll notice that at the center of that structure is a deep tunnel, one to two inches in diameter. These crayfish chimneys mark the entrance to a burrow that may extend as deeply as 36 inches. Crayfish breathe through gills and live their life in the safety of their flooded tunnels. However, living in a close space underground presents a problem. The water in burrowing crayfish tunnels doesn’t always get properly oxygenated like a moving creek does. The shape of the crayfish chimney is not just excavated dirt from the tunnels, but rather a carefully constructed ventilation system. Crayfish will build two crayfish chimneys at differing heights, causing air to be drawn in through the lower chimney and sucked out the updraft of the taller chimney. In between the two chimneys, our engineering crayfish’s water will be oxygenated.

It can be a bit of a mystery to many Parklands visitors that we have so many beaver-chewed trees, tracks, and beaver slides, but seemingly no beaver lodges or dams. Our beaver population, like many small stream ecosystems, has adapted to frequent flooding. Instead of building and rebuilding a home after every flood, our beaver families burrow into the stream banks. These are the largest holes you will come across and may be more than one foot in diameter. While they are quite large, they are often inconspicuous, emptying out near the water level of a deep pool. Like their cousin the chipmunk, beavers like to use the twining roots along the bank to disguise their entrance. Beavers will tunnel upwards from the entrance, and add upper and lower levels to their bank dens to allow for air pockets in times of floods, as well as an incomplete escape hatch that leads above the flood line for quick escape.

There are so many more marvelous natural engineers of underground construction. As you spend more time outside and hone your observation skills, you may start to notice intricate ant mounds, worm tunnels, the subtle grassy vole tunnels, and the heavily excavated fox dens. Each burrow tells a story of hearth and home for an animal. The more we can refine our identification skills, the greater our understanding of the interdependent lives of our field and forest neighbors will be.

your observation skills, you may start to notice intricate ant mounds, worm tunnels, the subtle grassy vole tunnels, and the heavily excavated fox dens. Each burrow tells a story of hearth and home for an animal. The more we can refine our identification skills, the greater our understanding of the interdependent lives of our field and forest neighbors will be.