Writer / Helen E. McKinney

John Floyd was an early settler of what is now St. Matthews. A pioneer statesman, surveyor, colonel in the Kentucky militia, and prominent in laying out the city of Louisville, Floyd can be remembered for many things.

He was born in 1750 in Amherst County, Virginia, to William Floyd and Abadiah Davis, both descendants of Welsh immigrants. He married early at the age of 18 to Matilda Burford, daughter of the sheriff of Amherst County. She died a year later giving birth to a daughter, Mourning Floyd.

By 1772, Floyd had moved to Fincastle County, Virginia. where he taught school and lived in the home of Colonel William Preston, his mentor. Preston was a distinguished figure on the Virginia frontier and surveyor for the western part of the state. Two years later he commissioned Floyd as a deputy surveyor and appointed him chief of a seven-member surveying party headed to the Falls of the Ohio. Kentucky was a part of Fincastle County at that time.

A member of the surveying party, Thomas Hanson, kept a journal of the experience. Hanson kept records of how the party met up with bands of Natives in the forest, dining on a feast of bear meat, of Floyd laying off 2,000 acres of land on the Cole River for Colonel George Washington, and of lands surveyed in what was to become Kentucky for Patrick Henry and other prominent men. Floyd’s mission on this trip was to make a survey of the bounty lands offered to veterans of the French and Indian War. Eventually Natives drove the party back to Virginia.

In 1775 Floyd came to Kentucky again, via the Cumberland Gap. During the following summer he was living at Fort Boonesborough and participated in the rescue of Jemima Boone, Daniel Boone’s daughter, in July of 1776. He returned to Virginia once more, but would make his way back to Kentucky in 1779 with several siblings and his new wife, Jane Buchanan, Colonel Preston’s niece. He and Jane had three children.

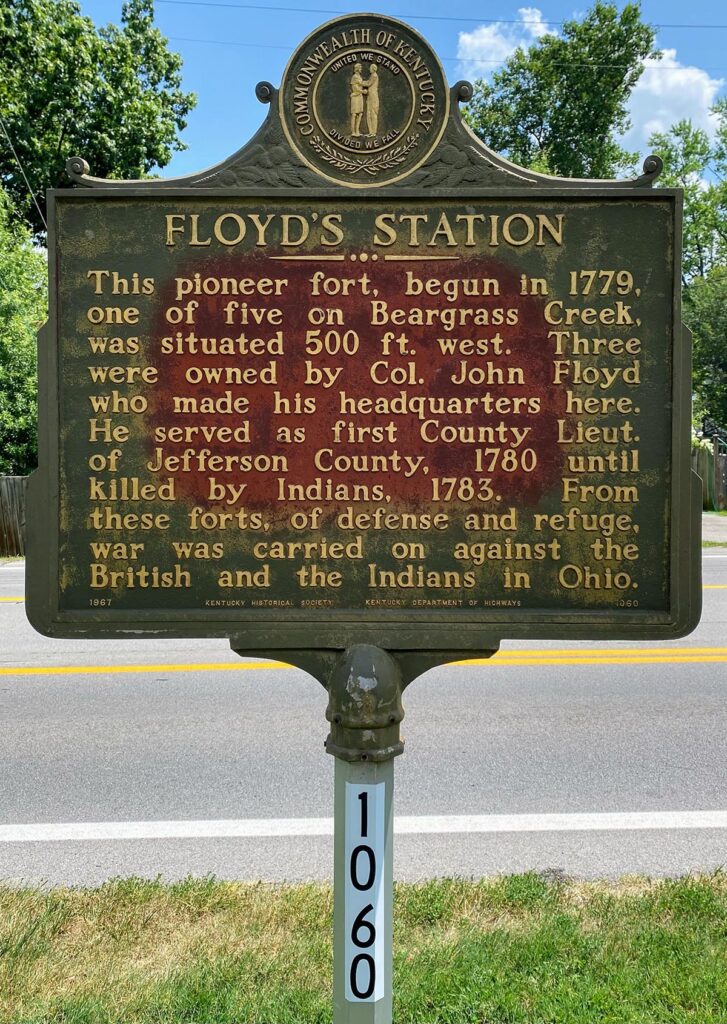

He had returned to claim 2,000 acres he had purchased in 1774. With his family, he built a cabin near Third and Main streets in present-day Louisville as a temporary shelter. He soon established a settlement near Beargrass Creek known as Floyd’s Station, in present-day St. Matthews near Breckenridge Lane, and 10 more families settled there with him. All that remains today of the station are a spring house and cemetery.

In 1780, by an act of the Virginia General Assembly, Floyd became one of seven trustees of Louisville, thus enabling him to assist in laying out the city. In 1781, General George Rogers Clark convinced Governor Thomas Jefferson to appoint Floyd as colonel of the Kentucky militia, justice of the peace, and surveyor of Jefferson County.

On September 13, 1781, a party of roughly 50 Miami Natives who had separated from a larger group two days earlier and were spurred on by the British, attacked settlers as they evacuated Squire Boone Jr.’s Painted Stone Station in Shelby County. The settlers were fleeing to Lynn’s Station, one of the Beargrass stations, and were attacked along the main ford of Long Run Creek, near the present-day site of the Eastwood Cemetery.

Several died but many also escaped and lived to tell their story of what became known as the Long Run Massacre. The following day, Floyd led 27 men to the Eastwood/Middletown site in a rescue and burial mission. When they reached their destination, they were ambushed. Floyd narrowly managed to escape and the incident became known as Floyd’s Defeat. Historical records have noted that he rode a fine black horse called Shawnee into the defeat.

The next day, a force of 300 men from the Falls and Beargrass stations marched to the area and buried the dead from the first massacre and from Floyd’s militia rescue in mass graves. At the site of Floyd’s Defeat, the bodies were buried in a sinkhole with stones and tree limbs placed on top, in an effort to keep wild animals away. The names of the dead were said to have been carved on a nearby beech tree.

Two years later, in 1783, Virginia leaders organized the government of Kentucky and Floyd was appointed to be one of the first two judges of Kentucky. Sadly, he would not live to see the land achieve statehood. He was wounded on April 8, 1783, by Natives while traveling to Bullitt’s Lick. He died of his injuries two days later. At the time of his death, he had been wearing a scarlet coat bought from Paris, which his widow, Jane, preserved until her death in 1812. She had requested the coat be buried with her. It is thought that Floyd was buried near the site of Floyd’s Station.

All that remains to mark these harrowing real-life events is a historical marker about the massacre, and a monument erected to Floyd and his men. The monument sits off in a lonely field on the backside of town. If you’re there on a still September day and listen closely, you can almost hear Floyd as he shouted and swore, when he and his militia rode out of Lynn’s Station, “The first man to lose his gun this day will be hung!”

Floyd is remembered annually along with survivors and those who did not survive at the re-enactment of the Long Run Massacre and Floyd’s Defeat at Red Orchard Park in Shelby County. This year’s dates include Friday, September 8 (School Day, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.; $4 per person – schools only). Saturday, September 9 is open to the public from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

On Saturday a battle reenactment takes place at 2 p.m, and the public is welcome to visit the settler and Native camps, see a live cannon demonstration, prisoner exchange, and various demos of 18th-century heritage skills. As a special tribute, the Sons of the American Revolution present colors and descendants are recognized, all in tribute to those who gave their lives to settle the Kentucky Frontier. Admission cost for the Saturday event is $6 per adult, $3 for ages 3 to 12, and free for ages 3 and under.

For more info, to read the story of Floyd and his involvement in the Long Run Massacre, or to register for School Day, visit paintedstonesettlers.org.