What Life Was Like in Jeffersontown During World War I

Writer / Beth Wilder

Photography Provided

It was called “the war to end all wars,” and thankfully, the Great War that broke out in 1914 Europe was not fought on American soil – but that did not mean Americans were spared the war effort. Even before the United States officially entered the war in 1917, Americans pitched in to help their European Allies in any way they could. The residents of Jeffersontown were no exception.

Area residents were fortunate. Aside from rising costs, they did not have to truly worry about the war when it first began. Of primary concern in 1914 was the fact that Christmas toys would have to be homemade, as none of the European countries were able to export any goods. By 1916 paper stock had gotten so expensive that The Jeffersonian editor, J.C. Alcock, feared the cost of his newspaper might have to increase, and insisted that those in arrears make their subscription payments or stop receiving the paper.

On May 25, 1916, a quote from the Germantown News must have prompted the townsfolk to take the war a little more to heart. Alcock was praised for the great success a special war edition of The Jeffersonian had, although the article went on to muse, “But maybe they are not affected by any of the conditions and calamities of the world’s big war act in that peaceful hamlet.” The next month, three local boys, Leroy Omer, Walter Zerger and Walter Ellingsworth, joined the Navy.

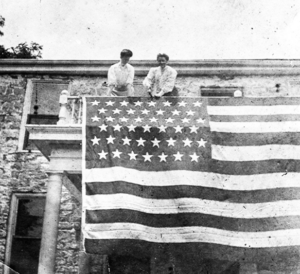

In May 1917 a meeting was held in Jeffersontown. Everyone was asked to assemble on the public square, carry the American flag and adorn their automobiles in patriotic colors. From there, the parade of cars drove to the schoolhouse, where over 2,000 people from different parts of the county assembled to hear various speakers urge young men to enlist, rather than wait to be conscripted into the military.

On June 5, 1917, all men between the ages of 21 and 31 were required to register for the draft. On July 26, the first list of draftees was printed in the paper, and in September, I.M. Huckleberry was the first Jeffersontown native ordered to Camp Zachary Taylor in Louisville. Dr. J.R. Shacklette was among the residents of Jeffersontown who were drafted, although he was sent Georgia to train in the Medical Reserve Corps, where he was commissioned as a first lieutenant.

Brother and sister Charles G. and Aileen Bryan, of Jeffersontown, were both ordered to France. Charles was commissioned a captain in the Engineer Corps of the United States Army, and Aileen, a member of the Red Cross staff of trained nurses, volunteered for field hospital service.

Those who remained at home in Jeffersontown were required to do their fair share toward the war effort as well. In October 1917, a group of more than a dozen Jeffersontown women canvassed the area to ask every householder to sign a pledge card to be as economical as possible, to help ensure those overseas had enough food. A Tobacco Fund was even created, so that “chews” and “smokes” could be forwarded to the fighting men in France.

Men who remained at home were encouraged to become Boy Scout leaders, so the young men in town would have a good influence and not risk becoming delinquents, as was happening in the war-ravaged countries. All boys were urged to join the Scouts, who served as dispatch bearers, delivering government pamphlets to all the local homes. In March 1918, boys aged 16 to 21 were asked to enroll in the Working Reserve, in the hopes that when they were out of school, they would assist with farm work or whatever occupation best suited them.

C.A. Hummel was the enrolling officer in Jeffersontown, and boys who signed on were eligible to receive a Federal Bronze Badge of Honor for a stated number of work days. Girls were also encouraged to join clubs that would help with raising food, and several prominent businessmen in town sold liberty bonds.

Meanwhile, residents were forced to tighten their belts. Food production was a priority – home canning and meatless days were encouraged. J.C. Alcock joked that a “taste” of food was about all he got, thanks to the conservation pledge the ladies signed.

Coal was hard to come by. The local paper noted in January 1918 that “every week or two a car load comes in, and is gobbled up before a third of the people get any.”

One particular group that suffered in a slightly different way was the local Germans. Jeffersontown was primarily settled by Germans, so a good deal of its populace had that ancestry – and some still retained their loyalty to Germany, especially if they had relatives fighting in the Kaiser’s army. The Jeffersonian newspaper noted that the majority of Germans in the county were loyal Americans, even if some of them did make “disloyal statements in regard to the war,” and that it was not right to say “mean things about the German-Americans because they are from Germany.” By the end of January 1918, however, all non-American citizens were required to officially register. Arch Bridwell, postmaster, conducted the registrations in Jeffersontown. Jeffersontown’s City Attorney Wallace A. McKay was selected by Washington, D.C., authorities to provide legal service at the various Army camps in the country, mainly concerning the registrations.

Red Cross units abounded, of course. The Current Events Club of Jeffersontown was just one of the groups who helped sew and knit hospital garments, trench caps, socks, sweaters and more. N.R. Blankenbaker, captain of Jeffersontown’s Red Cross forces, was happy to report his workers had raised $6,325 for the war fund – in today’s money, that would equate to over $43,000. Even children helped raise funds for the Red Cross by putting on shows, and they were also asked by Jeffersontown postman Lud Bryan to gather all the plum, peach and prune seeds, walnut shells, and hickory nut shells they could, to be used in the manufacture of gas masks.

Although three million men had already been drafted into service, in September 1918, another two million were deemed necessary. The enlistment notice stated: “Patriots will register. Others MUST.” By the following month, soldiers and civilians alike were fighting a new battle – an influenza epidemic. Nurses were in high demand, and by November, Jeffersontown was dealing with its highest number of cases to date.

Thankfully, on November 11, 1918, the armistice was signed, ending World War I. Jeffersontown’s duties to country were not over, however – relief was still needed both in the United States and throughout the world. Jeffersontown residents still had to bounce back from the flu epidemic, but they continued their support efforts through the reconstruction after the devastating war was over, doing their part as proud Americans, happy to have their boys home.