A tribute to Reverend Thurmond Coleman, Sr.

Photography Provided

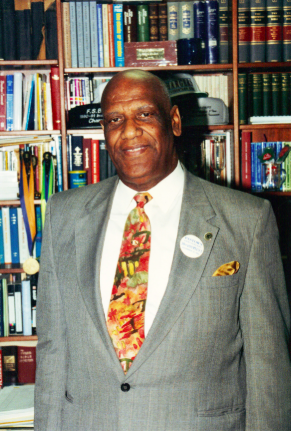

A giant of a man, with a deep, booming voice and jovial demeanor – that is the first impression Reverend Thurmond Coleman, Sr. made on others. It was natural to immediately feel at ease in his presence, but to hear him talk – no one could ever forget that, and one’s attention would be completely drawn in as he spoke, just hanging on to every word and how it was uttered. Whatever he said was riddled with a smattering of “Amens” and “Fine, Fine, Fines.” One could not help but adore him.

A giant of a man, with a deep, booming voice and jovial demeanor – that is the first impression Reverend Thurmond Coleman, Sr. made on others. It was natural to immediately feel at ease in his presence, but to hear him talk – no one could ever forget that, and one’s attention would be completely drawn in as he spoke, just hanging on to every word and how it was uttered. Whatever he said was riddled with a smattering of “Amens” and “Fine, Fine, Fines.” One could not help but adore him.

To list all of Coleman’s achievements and the honors bestowed upon him would take far more space than allotted here, but suffice it to say that he led First Baptist Church of Jeffersontown for 45 years, and he was very proud to have played a major role in establishing the Jeffersontown little league, high School and library, feeling that a good education was of the utmost importance to compete intellectually and economically. One of the gyms at the David L. Armstrong Recreation Center is named in his honor, as is the street where his parsonage was located. In the 1990s, when Skyview Park, which had been established by James Wilson in the 1940s for black children to have a place to play, was renovated and about to be renamed, Coleman was instrumental in making sure the name stayed the same. He was a civil rights activist and worked tirelessly to bring blacks and whites together as a community, not only in Jeffersontown but in the entire state as well.

Thurmond Coleman was born on September 19, 1926, in Logan, West Virginia. On the advice of his father, Reverend C.W. Coleman, Thurmond was urged not to work in the mines but to do something more with his life, so he prepared for the gospel ministry by attending Lincoln Institute, Central High School, Indiana Extension Center and classes at Southern Baptist Seminary. He was ordained at Clay Street Baptist Church in Shelbyville, Kentucky, and in 1955 he began pastor duties at First Baptist Church of Jeffersontown, where he would remain active as pastor for the next 45 years.

Reverend Coleman brought with him his wife, Cora Elizabeth, and their five young children, Jane, Thurmond Jr., Thelma, Charles and Donald. At a 2009 meeting of the Greater Jeffersontown Historical Society, Coleman noted, “When I come to Jeffersontown, the church, they said, ‘We’ll pay him $35 a week, and parsonage.’ I said, ‘Well, I’m not coming for the money,’ and the man said, ‘Well, that’s great – well, we’ll give him $30 every week.’ I’ll never make that mistake again!”

Reverend Coleman brought with him his wife, Cora Elizabeth, and their five young children, Jane, Thurmond Jr., Thelma, Charles and Donald. At a 2009 meeting of the Greater Jeffersontown Historical Society, Coleman noted, “When I come to Jeffersontown, the church, they said, ‘We’ll pay him $35 a week, and parsonage.’ I said, ‘Well, I’m not coming for the money,’ and the man said, ‘Well, that’s great – well, we’ll give him $30 every week.’ I’ll never make that mistake again!”

The parsonage was a gathering place for all the kids in the neighborhood, but it was not long before the family outgrew their home. Because of redlining Coleman had difficulty obtaining a larger house in Jeffersontown and had to move the family to downtown Louisville in order to buy a dwelling with more space. For the next fifteen years he had to commute – often several times a day – in order to fulfill his duties as pastor. In 1975 the Voice-Jeffersonian newspaper noted that as he addressed a heated gathering regarding racially-open housing, he “talked softly, telling the audience things it didn’t want to hear, and somehow he compelled them to smile and applaud at the end.”

Coleman faced many similar situations, often being the only black representative among a sea of angry whites, but all he had to do was start talking in order for others to calm down and listen. He believed strongly in community involvement, and spent many decades fighting racial injustices that had been so deeply ingrained in society. Early on in his tenure at First Baptist, he had to address the issue of the name of the church. At the time, there were two First Baptist Churches in Jeffersontown – one was a white congregation that ultimately built a sanctuary on Taylorsville Road, and the other was a black congregation that took over ownership of the old Union Church property at the corner of Shelby Street and Watterson Trail. When Coleman retrieved mail from the hardware store, he noted that all the envelopes said “First Baptist, Colored”. Coleman told the proprietor that if he couldn’t address his mail to 10600 Watterson Trail, he’d stop buying anything in the store. The proprietor agreed.

Coleman made a lot of difference in this town. In addition to serving as pastor of First Baptist, he also drove a school bus for Seneca and worked as a store detective at J.C. Penney. Many individuals who got caught shoplifting there noted how he saved them, because they knew they would have eventually ended up in jail had he not taken the time to minister to them personally. A 1978 Louisville Times article quoted him as saying, “I believe the whole person must be ministered to, not just his spiritual needs. There have to be rights and justice accorded folks on their jobs, and the church must lead in this.”

As pastor, Coleman led by a shining example. Faced with adversity, he remained calm and dignified, a figure to be admired, whether or not one agreed with his stance on matters. Coleman took care of his community – not just his flock at First Baptist Church, but the entire community.

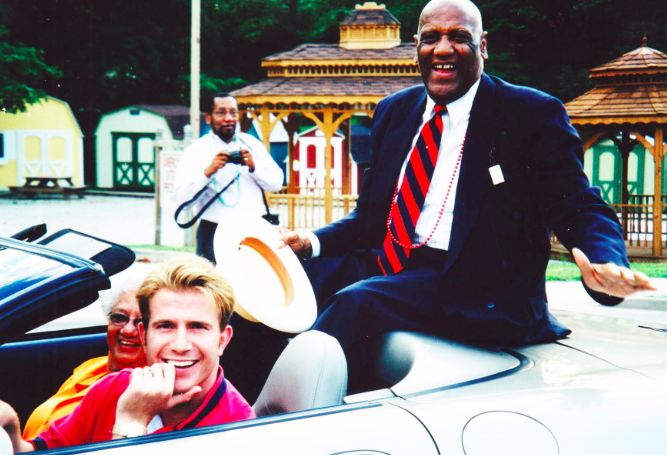

Reverend Coleman passed from this life on September 8, 2019. It seems fitting that he died right when the City of Jeffersontown – the community he served for over 60 years – was to celebrate the 50th anniversary of its hallmark Gaslight Festival. One of the highlights of his life was serving as Grand Marshal of the Gaslight parade in 2000 – his children said he got a kick out of waving to the crowd while riding in the Grand Marshal car. The family delayed putting his obituary in the newspaper until after the festivities were over, feeling that Coleman deserved to be honored without anything to detract from his memory.