As Memorial Day approaches, many Hoosiers’ minds turn to a unique location in the capital city of the Hoosier state, an iconic landmark representing not only Indianapolis, but all of Indiana.

You’d be forgiven for thinking the setup above refers to that most iconic of Indiana traditions, that of the Indianapolis 500. Incidentally, that race will take place, as always, at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, which, since 2019 has been owned by Roger Penske, a racing legend in his own right with a local connection – Penske attended Culver Academies’ summer Woodcraft Camp in his youth, graduating in 1950.

But let’s not forget on what weekend the race takes place. Memorial Day has been set aside since the end of the Civil War to remember those fallen in battle in various wars and conflicts. The legacy of the Civil War played a central role in the creation of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in the heart of Indianapolis, the first monument in the United States dedicated to the common soldier (rather than individual leaders).

Even if it’s impossible to overlook visually if one is anywhere near downtown Indianapolis (it holds the distinction of being the largest outdoor memorial in Indiana), it’s all too easy to overlook the monument historically, and its significance in honoring the contributions of Indiana’s veterans.

Even if it’s impossible to overlook visually if one is anywhere near downtown Indianapolis (it holds the distinction of being the largest outdoor memorial in Indiana), it’s all too easy to overlook the monument historically, and its significance in honoring the contributions of Indiana’s veterans.

The monument’s cornerstone was laid 135 years ago on August 22, 1889, though its formal dedication took place 122 years ago this month, on May 15, 1902, with a crowd of thousands on-hand alongside a parade of flags and veterans of the Mexican-American, Civil, and Spanish-American wars. Other central participants that day have regional connections to this area as well. Keynote speaker General Lew Wallace, a Crawfordsville native and author of “Ben Hur,” the bestselling book of the 19th century after the Bible, wrote parts of that book at Bass Lake and Lake Maxinkuckee.

“Hoosier Poet” James Whitcomb Riley read a poem written especially for the day, “The Soldier.” Among other connections, Riley was a visitor to Lake Maxinkuckee as well, and wrote a poem, “Life at the Lake,” about that body of water. Even internationally acclaimed bandleader and composer John Philip Sousa, who wrote a march entitled “The Messiah of the Nations” for the dedication ceremony, has a minor local connection. He composed “The Black Horse Troop March” in honor of the horses of the Black Horse Troop that would help bring fame to the Culver Military Academy.

The location of the monument holds its own significance in the history of Indianapolis. In the wake of the city’s founding in 1821, a three-acre plot of land was planned as the city center, with the intention that it would eventually house the residence of Indiana’s governor (the structure built for that purpose was never used for it, but instead was home to various entities including the Indiana State Library and State Bank of Indiana). The location was long used for outdoor public gatherings, especially in the years following the Civil War. A sculpture depicting Oliver P. Morton, Indiana’s governor during the Civil War, was dedicated there in 1884, though talk of a monument, especially one memorializing Indiana’s Civil War dead, was already underway at the time.

Of the 1,350,428 total state population in the 1860s, some 210,000 Union soldiers, sailors and marines from Indiana served in the war, with over 35%, or 24,416, losing their lives (that number eventually grew to 25,028 to include those who died of disease or longer-term wounds). Additionally, around 48,568 Hoosier soldiers were wounded.

The year 1875 saw a 10-year reunion of Hoosier veterans of the War Between the States held in Indianapolis, and during that event newspaper editor George J. Langsdale proposed a plan for the monument that was to come, with the Indiana Department of the Grand Army of the Republic raising over $23,000 over the next 12 years towards bringing the plan to fruition.

Appropriations made by the Indiana General Assembly joined with public donations, additional appropriations and added property taxes, to raise nearly $600,000 over the next 20 years to complete the project, which was begun in 1888 and continued over the next 13 years.

The monument’s design was called “Symbol of Indiana” and had been submitted to the state’s contest by Prussia-based architect Bruno Schmitz, a friend of monument commission secretary James Gookins. Schmitz was represented by deputy architect Frederick Bauman of Chicago, and a number of companies and individuals were contracted to construct the various aspects of the monument including its base, terraces, stonework, obelisk and sculpture work. Final installations for it were completed in 1901.

The monument’s design was called “Symbol of Indiana” and had been submitted to the state’s contest by Prussia-based architect Bruno Schmitz, a friend of monument commission secretary James Gookins. Schmitz was represented by deputy architect Frederick Bauman of Chicago, and a number of companies and individuals were contracted to construct the various aspects of the monument including its base, terraces, stonework, obelisk and sculpture work. Final installations for it were completed in 1901.

Reaching towards the sky is the central obelisk, made of oolitic limestone from quarries in Owen County, Indiana, with the figure of Victory crowning it. The monument measures over 284 feet high, only 15 feet shorter than the Statue of Liberty in New York. The actual Victory statue is some 30 feet tall, weighs 10 tons, and includes symbolic features such as a torch representing the “light of civilization,” an eagle representing freedom and a sword symbolizing victory. The statue took on the nickname of Indiana or Miss Indiana.

Elevator service to the glassed-in observation deck near the top of the monument dates back to 1894, though some steps are required to complete the ascent.

Pools, fountains and sculptures surround the base of the obelisk, and limestone tablets above its entryway doors, headed by the inscription “To Indiana’s Silent Victors,” commemorate the contributions of Hoosier soldiers to conflicts including the American Revolutionary War, the capture of Vincennes from the British in 1779, the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War and the Civil War, respectively.

Among the prominent sculptures surrounding the monument are “War and Peace,” “The Dying Soldier” and “The Return Home,” in addition to figures representing the artillery, cavalry, infantry and Navy at the monument’s base. Other sculptures include Revolutionary War hero George Rogers Clark, Indiana war hero and U.S. President William Henry Harrison, and James Whitcomb, Indiana governor during the Mexican-American War.

Electrical floodlights first enhanced the monument’s outdoor candelabra in 1928, and a tradition begun in 1962 dubbed “the world’s largest Christmas tree” involved the addition each year of lights and garlands strung from atop the monument to create the illusion of a huge Christmas tree, visible for some distance from downtown Indianapolis.

Eleven years later, in 1973, the monument was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

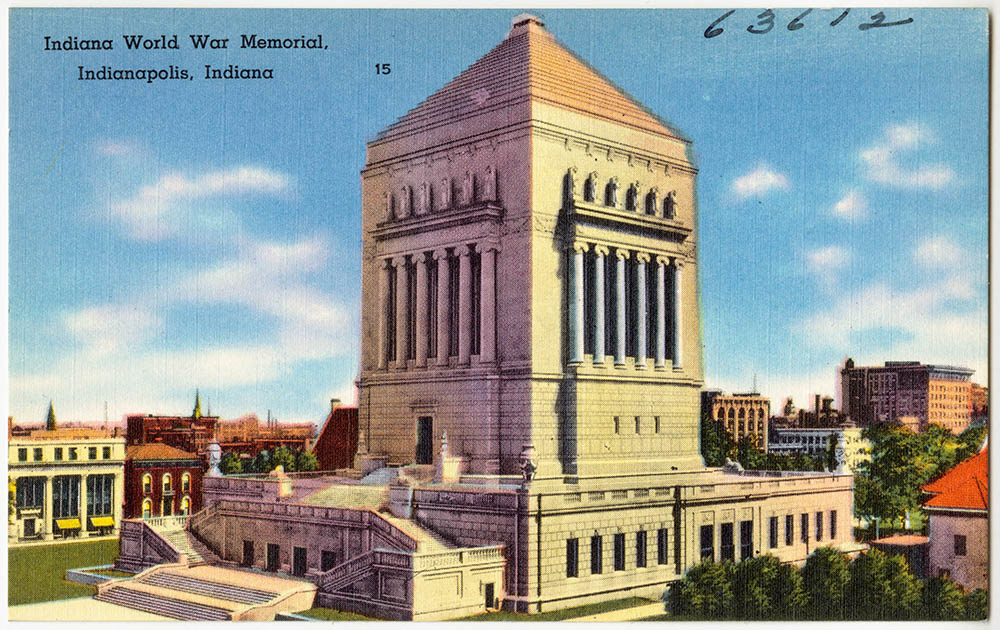

A museum focusing on the Civil War was added in the basement in 1918, though it has since been relocated to the Indiana World War Memorial museum and its attendant, five-block encompassing plaza, a site created after World War I located less than a mile from the Soldiers and Sailors Monument, and worthy of an article of its own.

A museum focusing on the Civil War was added in the basement in 1918, though it has since been relocated to the Indiana World War Memorial museum and its attendant, five-block encompassing plaza, a site created after World War I located less than a mile from the Soldiers and Sailors Monument, and worthy of an article of its own.

Of course the Soldiers and Sailors Monument is the centerpiece of the historic, brick-paved Monument Circle that forms the very heart of downtown Indianapolis and the city in general, and is part of a historic district including the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra and a host of notable establishments and buildings.

Since Memorial Day and the monument are our central theme, it might be worth noting some Indiana statistics relating to the major conflicts of the 20th century, in addition to the Civil War numbers referenced above.

-World War I: more than 130,000 U.S. soldiers hailed from Indiana to serve in “the war to end all wars,” over 3,000 of which perished. World War II: around 338,000 Hoosier men served in World War II, with 13,370 paying the ultimate price during the war. About 118,000 Hoosier women also served in the military in various capacities (not to mention the significant wartime contributions in Indiana-based manufacturing centers).

-Korean War: Some 85,000 Hoosiers served in the Korean War, with 742 having lost their lives.

-Vietnam War: Of the 136,000 from Indiana who served in Vietnam, 1,525 are listed as killed or missing in action.

Hundreds more Hoosiers have lost their lives in the conflicts since then, relating to the Global War on Terrorism.

So, if you’re attending that legendary Memorial Day event in Indiana’s capital city this year (or the next time you simply find yourself in its downtown), pay a visit to one of the most remarkable monuments in the state, and perhaps take a moment to appreciate the sacrifices of the Hoosiers who are among those whose sacrifices are commemorated each year on the last Monday of May.

Jeff Kenney is museum and archives manager for Culver Academies and one of the directors of the Historical Society of Culver.