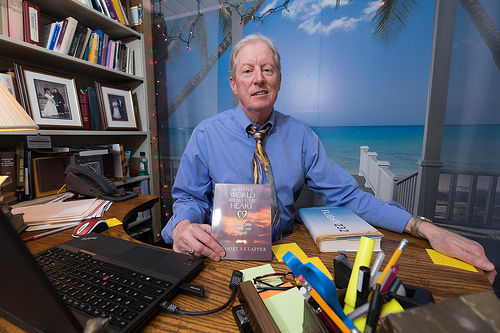

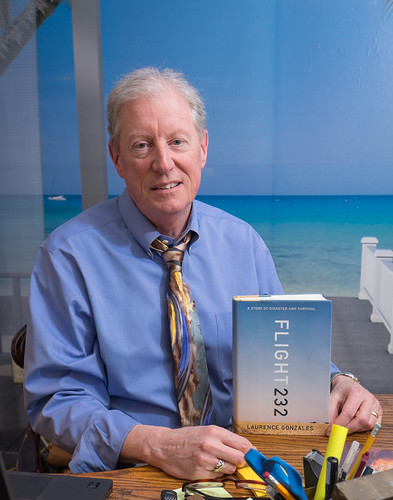

Writer / Joyce Long . Photographer / Chris Williams

Humidity radiated from the cornfields and hills — a typical summer afternoon in Sioux City, Iowa. To beat the heat, Greg Clapper had taken off Wednesday afternoon to take his family to the movies. He wanted his two young daughters to see Walt Disney’s version of “Peter Pan.” Walking toward the mall theater, his wife Jody and he stopped. A jumbo jet flew precariously low. Seconds later the ground vibrated. Smoke spiraled in the distance. United Airlines Flight 232 had crashed at Sioux City’s airport, July 19, 1989.

Fifteen minutes later, they arrived at the airport where police had already secured the crash site. At the roadblock, Greg handed the car keys to Jody. Instructing her to go back to the theater, he began running toward the airport a half a mile away. Commissioned three months earlier as a U.S. Air Force chaplain for the 185th Tactical Fighter Group of the Iowa Air National Guard, Greg wanted to help. With a doctorate from Emory University in theology, he was technically qualified. Yet Greg knew this catastrophe would be beyond a degree or textbook’s scope.

Originating from Denver, United 232 was en route to Chicago when its rear engine blew apart, causing the hydraulics to fail and the pilots to lose control. Those in the Sioux City control tower watched as the plane exploded into a fireball heading down the runway. The plane’s tail snapped off, its nose rising, and then bounced before it landed on its back in an adjacent field. (“Flight 232,” Laurence Gonzales. A short explanatory video can be found on YouTube: bit.ly/1zL14WE)

Baptism by Fire

More than 25 years later in his Greenwood home, Greg calls those ensuing hours “baptism by fire.” He remembers approaching the field with papers blowing everywhere, seats scattered, some filled with silent passengers and others empty. He spontaneously raised his hands to heaven, praying, “Lord, make me an instrument of your peace and help me to be your servant here.”

More than 25 years later in his Greenwood home, Greg calls those ensuing hours “baptism by fire.” He remembers approaching the field with papers blowing everywhere, seats scattered, some filled with silent passengers and others empty. He spontaneously raised his hands to heaven, praying, “Lord, make me an instrument of your peace and help me to be your servant here.”

No one witnessing the crash expected survivors. The 296 passengers and crew were presumed dead. Nevertheless, the unexpected happened. Flight attendants and passengers emerged, some injured, others simply shaken. An unmoving form that had flattened a few cornstalks caught Greg’s attention. Moving closer, he saw a man, injured but alive and conscious. After kneeling beside him, Greg said, “I’m the chaplain. Just keep breathing in God’s spirit, and people are going to be here to help you.”

“After they had taken all the injured off the field, my ministry focused on the uninjured,” said Greg. One of the flight attendants, Susan White, also helped survivors. He’ll never forget when Susan paused to call her father. “Dad, I’m alive,” she said. Her voice radiated humility and hope. Illustrating how close these rescue workers became, a few years later Greg co-officiated her wedding in Wadsworth, Ohio. “I was counseling survivors and rescue workers years after the crash during my time with the Iowa Air National Guard.”

Heart Religion

Heart Religion

Even before the crash, Greg gravitated toward what John Wesley called “heart religion,” a topic explored in his dissertation, “John Wesley on Religious Affections.” Early in his life, Greg felt called to ministry. “I was raised a Christian in a suburban Methodist Church outside of Chicago, the same church where Hilary Clinton grew up.” As a young adult majoring in philosophy and psychology, Greg experienced “an intensification of his faith.”

“I heard someone quote 1 Corinthians, Chapter 2, verse 5, which says you must trust in the power of God, not in the wisdom of men,” said Greg, who redirected his study and received a Master’s of Divinity and eventually his PhD in theology. “I took those interests into the world of faith, which led me to combine academics with my personal faith.”

In 1998 after accepting a professorship at the University of Indianapolis (UIndy), Greg, Jody and their two daughters, Laura and Jenna, moved to Greenwood. He currently teaches religion and philosophy courses at UIndy. “I love teaching. I see this as a great ministry, to teach students that Christianity is still a live option,” said Greg. “Christianity is a way of life. You don’t have to think of it as a doctrine, a creed or even a book.”

A well-known John Wesley scholar, Greg also teaches a two-course sequence at Christian Theological Seminary (CTS) focusing on the history and doctrine of the Methodist Church. In 1997, he published his first book, “As If the Heart Mattered: A Wesleyan Spirituality” through Upper Room Books, Nashville.

In understanding heart religion, Greg quotes one of Wesley’s letters, “I regard even faith itself not as an end, but as a means only. The end of the commandment is love — of every command, of the whole Christian dispensation.” (p.100)

After the Battlefield

During Greg’s 24 years as a commissioned officer with the Air National Guard, he volunteered for military deployments five times. The first happened the spring of 1995 in Turkey, counseling a fighter unit after the Gulf War. For three stints during 2005-07, Greg served as the chaplain on the psychiatric ward of the U.S. Army’s Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany, where wounded soldiers from Iraq and Afghanistan are brought before returning to the U.S. In the summer of 2008, a slot opened in Guam. Greg signed up, anticipating a more leisurely, less stressful deployment in an “island paradise.” He smiled when adding, “While I was there, a B-52 crashed.”

As a chaplain, Greg has looked tragedy in the eye and tried to make sense of it. “Tragedy really comes as a mystery into our lives, but there are resources in our religion that help us not to suppress it but to move through it. It helped me become a more humble and an attentive presence in the midst of heartbreak.”

Greg’s second book, “When the World Breaks Your Heart,” speaks directly to spiritual ways of living with tragedy. In Chapter 5 entitled Hope, he explains why people attended the anniversary memorial service for Flight 232. “Some came to see where their relatives had died. Some came to thank those who helped pull them from the plane. Some were workers who had pulled the dead and dying and survivors from the plane. Some came to cry. Some came not knowing why.” (p.73)

“Dad, I’m Alive!”

Before the memorial service, Greg had hoped Susan White would attend. Helping her call her father and hearing her say, “Dad, I’m alive,” impacted Greg. “The Thanksgiving that was part of that worship service is directly linked to those basic words, naked in their primitive joy: ‘I’m alive,’ those words which seem to say ‘Thank you, God, for this beautiful and deeply mysterious gift.’” (p.75)

Teresa Kilburn, a computer operator for the Air National Guard, also helped when Flight 232 crashed. Greg and she forged an ongoing friendship and a counseling relationship that helped her navigate out of a downward spiral of abuse and addiction. Like Susan, Teresa asked him to help during her wedding a year after the crash. But Greg was shocked when she asked him to give her away because her father had died. “My walking her down the aisle symbolizes our relationship,” said Greg.

As a chaplain and professor, relationships are important to Greg. He seeks to listen, be real and move people toward a future of hope, one that celebrates life.