Writer / Kara Reibel

Writer / Kara Reibel

Photographer / Brian Brosmer

When Sarah Brown’s daughter Emily Burke had her first heart surgery, she was three days old. Emily was born in Lafayette but was taken by ambulance to a hospital in Indianapolis the day after she was born. The first pediatric heart surgeon at Riley at that time (1967) had been there two years and had told the Browns that Emily may not survive.

With a congenital heart defect like Emily’s (pulmonary atresia), surgery is immediately required to correct the situation. “But this isn’t a cure,” shares Brown. Emily had another defect, a ventricular septal defect (hole in the heart) that required another surgical procedure when she was 3. After this surgery, she stayed at Riley for a six-week recovery. She had her final pediatric heart surgery at age 13 and has led a fairly normal life.

As adults, there are other challenges. Emily almost died seven years ago and required an implantable cardiac defibrillator. Her official diagnosis was ventricular tachycardia.

“Things are different today,” shares Brown. “The doctors know more, and many of the congenital defects are repairable, but this doesn’t imply a cure. These kids require lifelong care.”

This experience inspired Brown to start the Congenital Heart Walk in Indianapolis to raise awareness of those living with a congenital heart defect. The walk is May 21 at Butler University.

“Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the number one birth defect in infants,” says Brown. “Today the defect is often detected while the baby is in utero, and parents can prepare, but there is still a long way to go.”

Last year’s event raised $50,000 for two advocacy organizations, including the Children’s Heart Foundation which awards 10 CHD research grants each year. One of these grants was given to Dr. Mark Rodefeld, pediatric heart surgeon at Riley Hospital for Children.

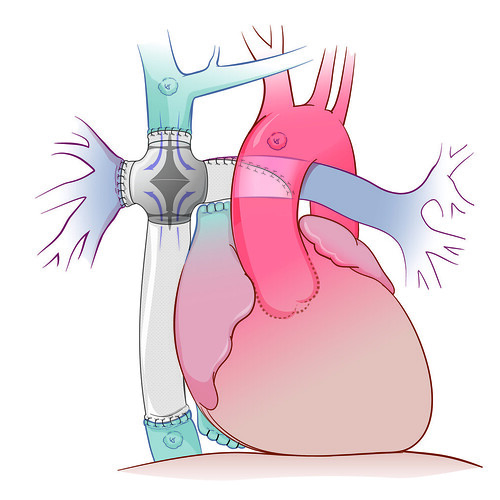

Dr. Rodefeld has designed an internal heart pump to assist blood flow in some of the most severe heart defect cases where someone is missing half of their heart. This occurs when a child is born with a structural defect in which one or more of the two lower heart pumping chambers has failed to form.

Dr. Rodefeld has designed an internal heart pump to assist blood flow in some of the most severe heart defect cases where someone is missing half of their heart. This occurs when a child is born with a structural defect in which one or more of the two lower heart pumping chambers has failed to form.

These cases are referred to as single ventricle congenital heart disease. Currently, the treatment for a child born with a single ventricle is three open-heart surgeries and often still results in a heart transplant down the road. Scott Leezer is now an adult who was born with this condition. Healthy hearts have two pumping chambers; Scott has one.

Leezer has experienced two open heart surgeries, one when he was 2 1/2 and the other at 24. He has had eight pacemakers over his 29 years. Based on his life experience with CHD, Leezer was drawn to become an advocate and began working with Senator Durbin in Washington, D.C., whose daughter was born with CHD. As a Health Policy Aide to the Senator, Leezer met with advocacy groups who sought to create a stronger voice for change.

“It was challenging,” recalls Leezer, who now lives in Indianapolis. “CHD is the most common birth defect and a leading cause of infant mortality, yet it felt like the advocates for CHD were in the minor leagues compared to other groups with much more money.”

With the Congenital Heart Walk, thanks to Dr. Rodefeld and his research, the money raised by the Walk stays in Indiana. Dr. Rodefeld’s grant was $100,000, but for the expensive nature of the device he has created, much more is needed to move the device forward to trials and improvements.

“Prototyping a device is expensive,” says Dr. Rodefeld, who is actively seeking additional funding to offset costs associated to further the development and research for his early stage device. “Once this device is perfected, it would help someone like Scott, replacing the missing half of his heart.”

At the current rate, Dr. Rodefeld’s device (the Fontan blood pump) is five to 10 years away from approval. Blood pump prototyping and regulatory approval is expensive, and it’s a lengthy and expensive process for regulatory checks and filters.

When a baby is born with CHD, the treatment is not a simple answer as to how many surgeries that child may need to experience. There are nearly 40 different types of heart defects at birth ranging in complexity.

“Some have multiple surgeries, some need a transplant, some have zero surgeries,” says Dr. Rodefeld. “It’s truly case by case, and it’s a fairly complicated group.”

Visit congenitalheartwalk.org for more information. You can donate to Dr. Rodefeld’s research, “Cavopulmonary assist for single ventricle heart disease research fund,” through IU Foundation by emailing hgilroy@iu.edu.