Writer / Beth Wilder, Director Jeffersontown Historical Museum

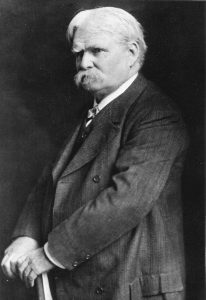

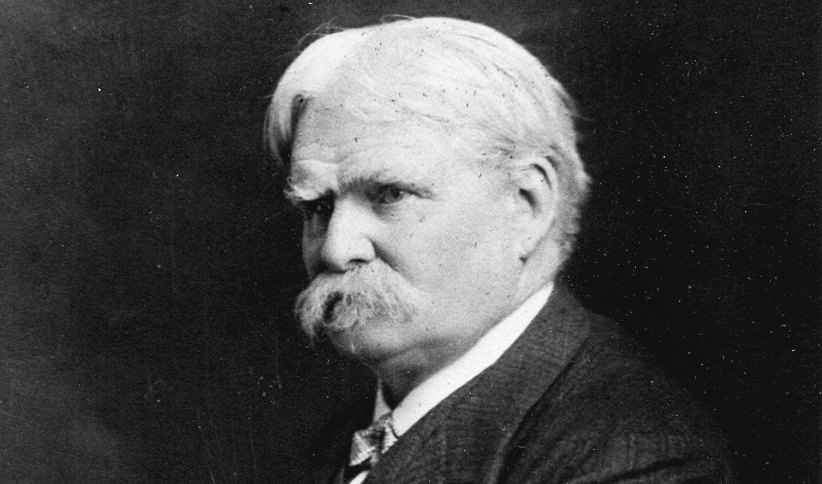

Jeffersontown has had several noteworthy residents throughout its history, but none quite so renowned as Henry Watterson, the famed editor of the Courier-Journal newspaper.

Jeffersontown has had several noteworthy residents throughout its history, but none quite so renowned as Henry Watterson, the famed editor of the Courier-Journal newspaper.

Watterson (Feb. 16, 1840 – Dec. 22, 1921) was a legend in his own time, rubbing elbows with society’s elite and making a name for himself by writing colorful and controversial editorials that appeared in newspapers across the country. Watterson also served as a Democratic representative in Congress from 1876-77 and became widely known as a lecturer and orator.

Watterson’s Jeffersontown connection existed the last 27 years of his life. In 1894, he purchased land on the outskirts of town that was owned by Joseph Hite, a descendant of one of Jeffersontown’s pioneer families, and proceeded to transform the house and property into a grand estate. Watterson left the original 4-room log house on the property intact, but proceeded to add to it until he had created a magnificent, 28-room mansion he named “Mansfield” after his wife’s childhood home in Nashville, Tennessee.

During his years at Mansfield, Watterson was visited frequently by former presidents, congressmen, statesmen, writers, actors and musicians, including one of his very best friends, vaudeville entertainer Eddie Foy, father of the “Seven Little Foys.”

Watterson had been in the newspaper business since he was a young man, and he became known for his fiercely independent nature and caustic political writings. During the Civil War, although he served as a Confederate due to his strong belief in states’ rights and loyalty to his home, he was not a proponent of succession or slavery. He had no problem criticizing General Braxton Bragg in his articles, and the general wanted to have him arrested for treason. Still, his views during the Civil War made him a well-known figure, and he became editor of the Nashville Banner when the war ended, bringing the paper back to respectability after being virtually closed down for four years.

Not long after that, George D. Prentice, owner of the Louisville Journal, approached Watterson and offered him half ownership and a job as chief editor, in the hopes of reviving the paper’s waning popularity. Walter Halderman, owner of the Louisville Courier, also offered Watterson an editor’s job and some stock – but no ownership in the paper – so Watterson accepted Prentice’s offer instead. He did, however, suggest merging the two papers, but Halderman declined the proposal.

Watterson quickly brought back the Louisville Journal to its former prominence, and his editorials were a source of great interest throughout the country. Watterson again proposed a merger with Halderman, who this time accepted, and on November 8, 1868, the Courier-Journal was born. Watterson was chief editor and had a free hand in what to write.

He did not like the business side of newspapers, so gladly gave up all but 75 shares of the new Courier-Journal. Yet the value of these shares was $75,000, an enormous amount in those days, and his salary was $10,000 a year, a sum virtually unheard of, even for New York editors at the time. Watterson had just enough shares of the newly established paper to make his personal life very comfortable and his professional life free from interference with his independent nature and ideas. Watterson would remain with the Courier-Journal for more than fifty years, making it one of the most prominent and influential papers in the country.

Once Mansfield was ready for habitation by the Watterson family in 1896, Henry used it as his home office, penning his articles there in the morning, then riding the interurban into the Courier-Journal’s Louisville office. The drive from Mansfield into the square in Jeffersontown where Watterson boarded the interurban became known as “Watterson Trail.”

Several local residents worked for Watterson. James Wilson, Sr. was Henry Watterson’s beloved butler, and his wife, Belle, sometimes acted as housekeeper – their son James Jr. grew up to be the founder of Skyview Park in Jeffersontown. Watterson’s cook, Hattie Harris, once owned the Leatherman cabin at 3606 College Drive. And in 1908, there were two Henry Wattersons in Jeffersontown – a man named Henry Watterson from Newark, New Jersey served as gardener for the great editor.

Watterson loved living in Jeffersontown. One of his favorite quips was, “I’m a Jefferson Democrat. I live in Jeffersontown in the county of Jefferson.”

Jeffersontown residents knew Watterson as a gentle, friendly neighbor, while most of the country viewed him as a hard-hitting, no holds barred newspaper editor.

At age 74, Watterson’s career reached its zenith. War broke out in Europe in 1914, and Watterson took a decidedly anti-German stance in the conflict. Other papers in town tried to remain neutral, to avoid offending the rather large German population in the area, but Watterson continued with his assertive articles in support of the United States entering the war, eventually earning the paper a Pulitzer prize. As much as World War I brought Watterson added fame, however, it also caused his career to wane. His relationship with the Haldermans became strained, and the paper lost subscriptions because of people protesting his editorials at the time.

At age 74, Watterson’s career reached its zenith. War broke out in Europe in 1914, and Watterson took a decidedly anti-German stance in the conflict. Other papers in town tried to remain neutral, to avoid offending the rather large German population in the area, but Watterson continued with his assertive articles in support of the United States entering the war, eventually earning the paper a Pulitzer prize. As much as World War I brought Watterson added fame, however, it also caused his career to wane. His relationship with the Haldermans became strained, and the paper lost subscriptions because of people protesting his editorials at the time.

The paper was sold to Robert Worth Bingham in 1918, and Watterson was asked to stay on as “Editor Emeritus,” penning editorials whenever he wanted, on whatever subject he chose.

Watterson retired from the paper in 1919, settling down to a happy and peaceful life at Mansfield. He passed away in 1921 while wintering in Florida. His wife, Rebecca, remained at Mansfield until her death in 1929. Other family members lived in the old mansion, but gradually moved away as the house fell into disrepair over the years.

Watterson’s daughter, Mrs. Bainbridge Richardson, had hoped to see Mansfield turned into a shrine in memory of her father. While there had always been an interest in the project, something always seemed to happen to prevent it. The family received somewhat of a consolation in 1960, when an expressway was named for the great editor.

His estate, however, continued to deteriorate while people argued about what to do with it. In 1963, Marion Miller, Watterson’s grandson, had hopes that Mansfield would be selected as the site for the proposed Louisville zoo and offered $25,000 to go along with James Graham Brown’s $1,500,000 donation for the attraction. Local residents did not like the idea of the noises or smells a zoo would bring to their tranquil town.

Several groups had differing plans for Mansfield, including residential development. Many legal entanglements ensued, keeping anything from happening to the estate, as it grew ever more dilapidated. Meanwhile, the house repeatedly fell prey to vandals, and on the evening of Thursday, October 6, 1975, Mansfield was badly burned in a fire.

The second and third floors were gutted, and the cause was listed as arson. No one ever knew for certain exactly who set the fire, although police at the time highly suspected teens who were constantly to be found there.

Eventually, Watterson Woods subdivision was established on the site of the estate of the most outstanding personality ever to reside in Jeffersontown. Although no tangible shrine to Watterson was ever created, his legacy remains strong not only in Jeffersontown, but in the whole of Jefferson County and nationwide as well.

The outspoken editor of the Courier-Journal made himself a part of history, and Jeffersontown is proud to have been the place he called home.

Comments 3

I have a photo of the newspaper clipping of my grandparents getting married in the Watterson Hotel..I never heard of it and had to find out information about it. So very sad they demolished it.. My Daddy was also born in Owensboro..

Recently found Mr Wattersons horse carriage at Heritage Antiques in Lexington