School Resource Officers Make Learning Safer

Writer / Christy Heitger-Ewing

Photographer / Amy Payne

Following the school shooting in Parkland, Florida, in February of 2018, there was a nationwide push to get police officers into schools. While some schools hired security guards or reserve officers, the Plainfield Community School Corporation went in a different direction, choosing to hire school resource officers (SROs) employed by the Plainfield Police Department (PPD) to not only keep each campus safe, but also build relationships with students and staff.

Following the school shooting in Parkland, Florida, in February of 2018, there was a nationwide push to get police officers into schools. While some schools hired security guards or reserve officers, the Plainfield Community School Corporation went in a different direction, choosing to hire school resource officers (SROs) employed by the Plainfield Police Department (PPD) to not only keep each campus safe, but also build relationships with students and staff.

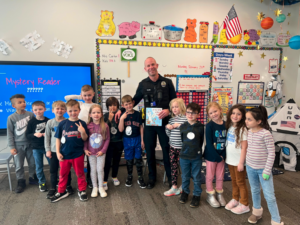

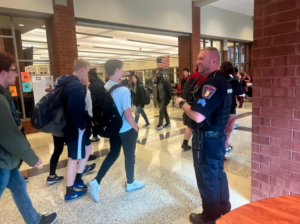

Two officers initially became full-time SROs at the Plainfield schools. Today that number has grown to six. John Endsley is at the high school and Josh Jellison is at the middle school. Chris Duffer splits his time between Clarks Creek and Brentwood elementary schools. Scott Poston divides his time between Central and Van Buren, and Aaron Teare is at Guilford. Nate Nolin serves as supervisor for the SROs. This seasoned group of SROs has been working in law enforcement for more than two decades.

Nolin’s oldest child was a kindergartener when the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting happened. Nolin vividly recalls dropping off his daughter at school the next day.

“I almost couldn’t leave the parking lot,” Nolin says. “It hit me that this sort of tragedy could happen anywhere.”

Having SROs in each school building helps to alleviate that worry.

Prior to becoming an SRO, for eight years Nolin worked the night shift for the PPD.

“When I worked nights, with my rank, role and position I had a high degree of influence with a low degree of visibility,” says Nolin, who has three children in Plainfield schools. Nolin likes the fact that the SROs are not school employees, but rather officers from the PPD.

“Here at the schools I have a high degree of visibility with the same type of influence, but I’m around a younger generation,” he says. “Sometimes the goal of a school corporation and the goal of a police department don’t always equal the same thing. We have veteran officers who have served in a multitude of roles within the department, who have become subject-matter experts in prioritizing the most important hierarchy of what needs to be done.”

SROs ensure student safety as they come in each morning, clear egress routes for busses, and monitor traffic flow. Once the bell rings, officers start securing the buildings and locking all doors. Officers pay attention to whether a kid is having a rough day or is not expressing normal enthusiasm. If concerns arise that may require criminal law investigations or child protective services, SROs share those concerns with the principal.

Aside from these safety issues, one of the primary roles of SROs is to listen when students want to share about their life – from the superficial to the serious. Sometimes students seek out SROs for advice. Others open up about trouble at home.

“One kid might tell me about her boyfriend,” Endsley says. “Another may tell me about the speeding ticket he got. They come to me because I’ve earned their trust.”

In 2018 Endsley was named Officer of the Year. It’s a coveted honor because the award is chosen by fellow officers who vote on someone who has gone above and beyond the call of duty to help build relationships in the community, has done something that was life-saving, or has helped improve policy.

“John started at the high school three years ago, so the students who were seniors then are finishing up college now and soon may be starting families,” Nolin says. “He’s going to be a generational influence.”

This past spring there was a bank robbery in Plainfield that occurred within a mile of two of the schools. As a precaution, the SRO on-site immediately got all students inside the building. He closely monitored the situation and as soon as the threat had passed, the students resumed their day.

“When you have an issue or any type of safety drill, having an officer who is calmly monitoring the situation can really bring down the tension to where the learning environment can continue,” Nolin says.

When kids graduate from one school to the next, they know they’re still in a safe place because while they’re leaving one officer, they are heading into a school with another one. For years Todd Knowles, who recently retired from the force, ran the D.A.R.E. program for Plainfield schools.

“He made such an impact teaching D.A.R.E. to the middle school kids,” Endsley says. “Talk about bridging gaps. He would get questions about drugs and alcohol, addiction, and body safety.”

When Knowles would visit the high school, students would come up to him all the time because they adored their D.A.R.E. officer.

“It’s cool to see how officers impact these kids,” Endsley says. “It’s definitely a team effort.”

“It’s cool to see how officers impact these kids,” Endsley says. “It’s definitely a team effort.”

Endsley works hand-in-hand with the guidance department and school administrators any time a tragedy occurs at the school or in the community. He then helps organize crisis response teams. For instance, if a student is involved in a crash, fatality or suicide, Endsley is called, and then he contacts Principal Pat Cooney to relay the incident.

The crisis response team, which may consist of folks from all around Hendricks County and beyond, come into the school to offer emotional support. They set up different points in the building where those who are struggling can talk.

“Pat cares a lot about these kids,” Endsley says. “He goes over and above to make sure everything is getting addressed. My role is to assist him in anything he needs in the building, from site security to making sure I’m in the hallways identifying kids who are emotional and giving them the help they need. We are a support to the school essentially.”

At the beginning of the year, each building officer meets with school safety specialists to identify the areas that need to be addressed and sign off on the national checklist. Indiana House Bill 1093, which makes changes to the definition of “school resource officer,” will soon be implemented, and the measures the bill seeks to make into requirements are measures Plainfield has already been doing.

“We’ve been operating as a best-practices standard for several years now,” Nolin says. “We like it when state law comes out of things that we were already doing.”

Nolin previously worked in criminal defense. He was inspired by his wife, who is a firefighter, to become a police officer. Now he sees cases in some form similar to what he was dealing with before, but from a completely different angle. Though he admits that some days are rough, he says there is no career that is more rewarding. Endsley agrees.

“Here in the school I see these kids grow from the time they come in as freshmen to when they leave as seniors,” he says.

When they enter as middle schoolers they still have maturing to do, but as they find their way, they become leaders in sports, clubs and activities.

“That all gets them ready to graduate, enter the workforce, join the military or leave for college,” Endsley says. “That’s uplifting.”