First Integrated High School Team in Indiana Reflects Unique History in Culver

Writer / Jeff Kenney

Photography Provided

Culver High School (CHS) quietly made Indiana and national history a century ago in an unlikely venue – on the hardwood of the basketball court.

Though no mention was made of it in publications of the day, thanks to the presence of two players, identified only as Whitted and Wade in the pages of the Maxinkuckee yearbook, the 1922 CHS basketball team was the first integrated high school basketball team in Indiana.

Graduation records indicate the two black players pictured must have been Wesley Wade, in the class of 1923, and Palmer Whitted, in the class of 1924. Another indication lies in the results of a 1936 survey undertaken by the Culver Citizen newspaper for fans to pick players for an all time CHS team of the greatest players the school had produced to date. Whitted and Wade both made the short list, with Wade receiving more votes than any other player.

The Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame confirmed the team’s integrated status and published an article about it in 2009.

In many ways, that unique status should come as no surprise. The first black graduate of Culver High School, Clara Rollins, accepted her diploma at graduation exercises in May of 1906 – a remarkably early date for a school, especially a small, rural Midwestern one, to include an integrated population. Even more remarkable was Rollins’ graduation speech, as reported in The Culver City Herald newspaper, which described a speech she gave during the commencement ceremony as “an instructive and thoughtful review of the development of the colored people of the South since the civil war.”

More to the point, the Herald reported that Rollins’ speech reflected her belief that “the time will come when the negro will not be socially ostracized” – an amazing prediction made decades before it began to come to fruition in the U.S.

The earliest permanent members of what would become a thriving black community in Culver through the mid-20th century arrived on the shores of Lake Maxinkuckee in the late 1890s, many of them members of the staff of the Missouri Military Academy in Mexico, Missouri, which burned down in 1896.

Culver Military Academy Founder Henry Harrison Culver, whose school had recently opened in 1894, found his fledgling student population a bit on the small side and wired the Missouri school’s superintendent, Alexander Fleet, with the following message: “We have the buildings, you have the boys. Let’s get together.”

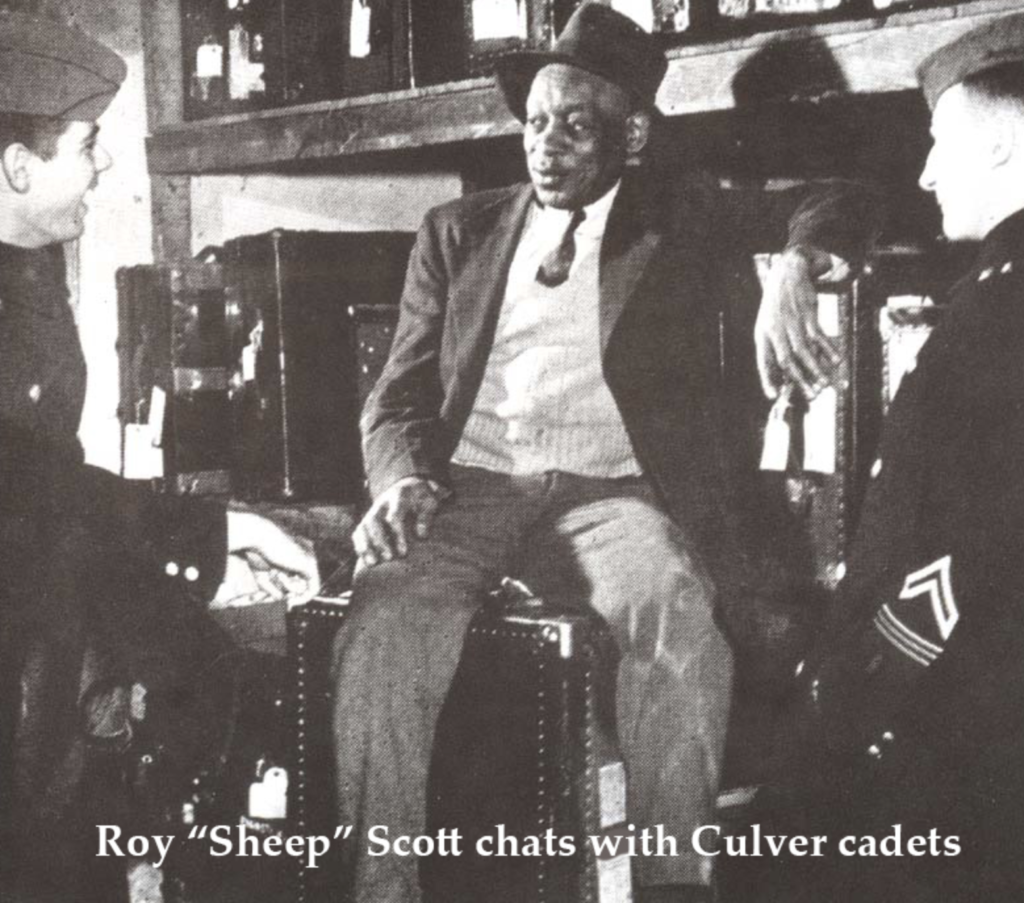

Besides his teaching staff, Fleet brought trusted members of the school’s support staff, with more to follow. Eventually, Culver Military Academy’s staff included a number of black employees including several who became pillars of the local community. Among these were Roy “Sheep” Scott, a custodian and unofficial counselor to generations of cadets, and Charles Dickerson, head of the bustling Mess Hall waitstaff at the school. A bust of Dickerson holds a prominent place at Lay Dining Center on the academy’s campus today.

Scott was an esteemed member of the Culver community at large as well, known for gathering castoff sports equipment left behind by academy cadets to distribute to less fortunate children of all races in the community, and for his local baseball and softball coaching prowess.

Additionally, a number of Lake Maxinkuckee cottagers employed black staff members, leading to a thriving black middle class in the Culver area.

That reality can be seen in several unusual local endeavors. The Entre Nous Club (from the French meaning, “between us”) was comprised primarily of longstanding members of Culver’s black community, and combined social events similar to those popular, particularly among women, during the early- to mid-20th century. Tea and refreshments were served, conversation held and community outreach undertaken, including occasional dinners provided for members of the temporary black staff employed by Culver Academy during the summer months, and housed in small structures off-campus known as the shacks.

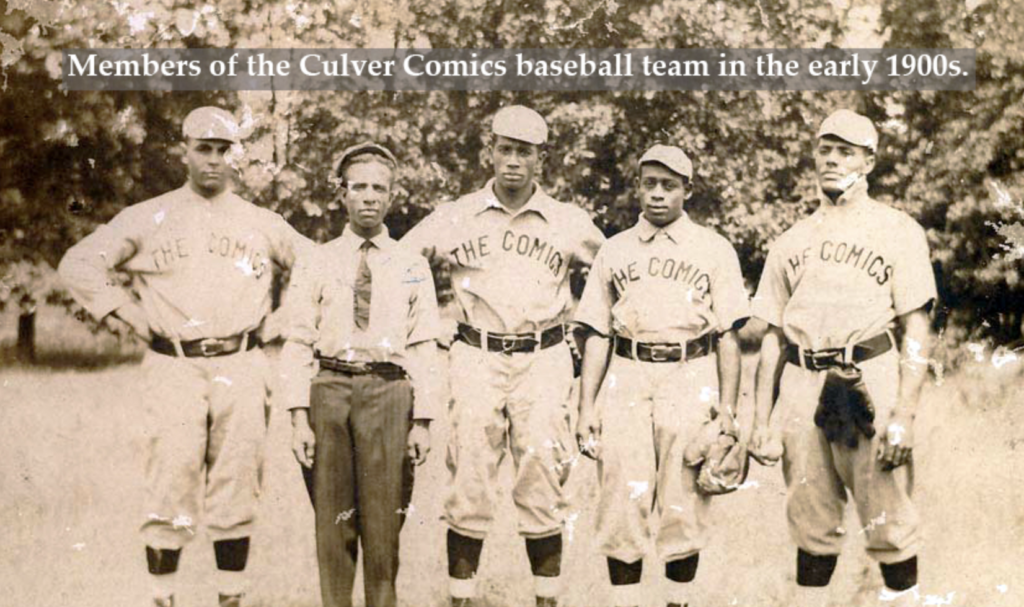

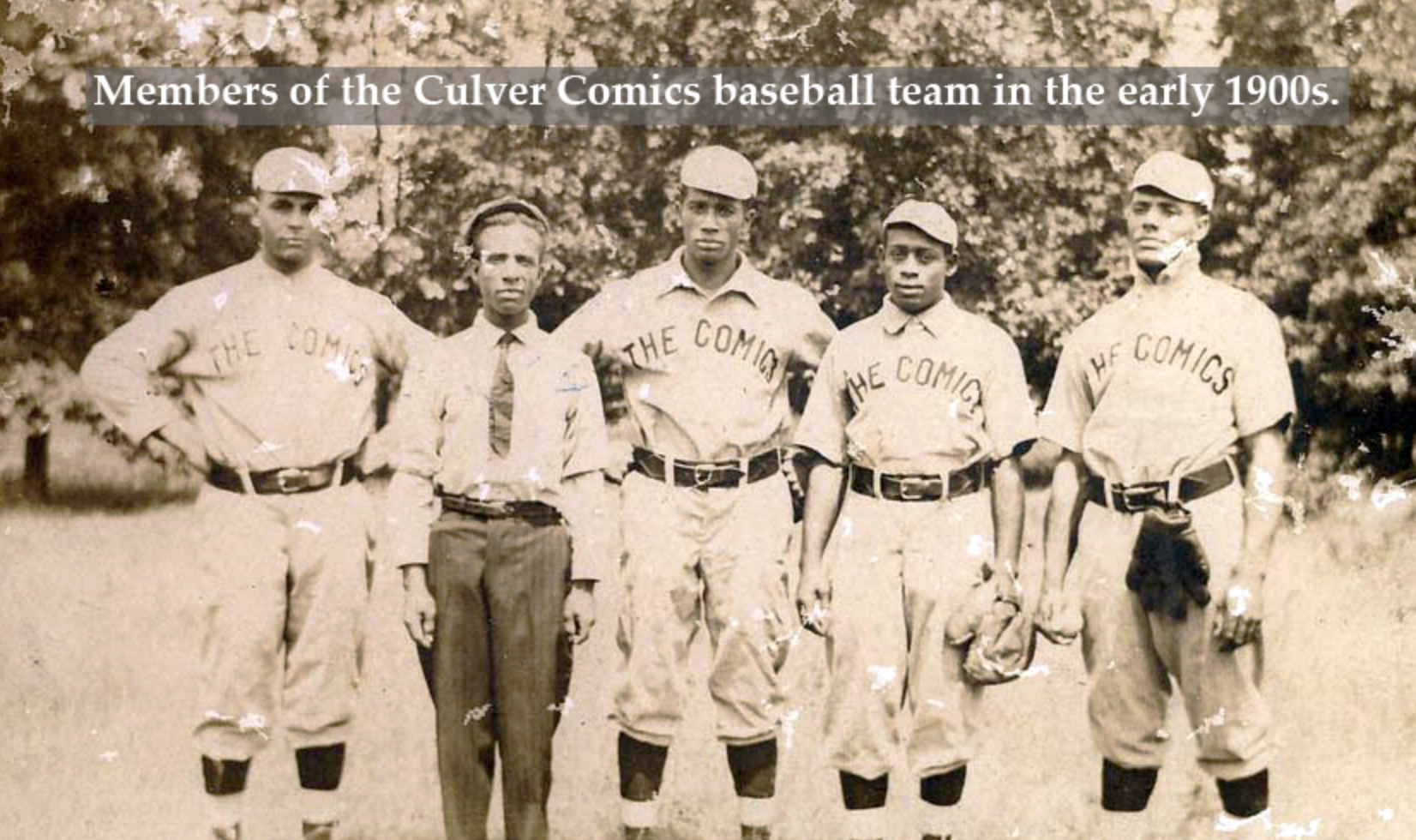

Members of the academy staff formed a popular traveling baseball team, the all-black Culver Comics, modeled after the popular Negro League teams of the day (such as the Indianapolis Clowns – similar to basketball teams like the still-popular Harlem Globetrotters). Exhibition games drew crowds in the thousands as well as fairs and picnics around the region.

Clara Rollins’ father George, a member of Culver Academy’s staff, donated land near today’s Lake Shore Drive and Coolidge Court in Culver to start a church focused specifically on the spiritual, relational and material needs of the local black population. Rollins Chapel opened in 1913, eventually became a member branch of the African Methodist Episcopal denomination and operated into the late 1960s.

Many of Culver’s black families of this period saw their children and grandchildren go on to levels of education and career status not only unusual for African Americans in the mid-20th century, but also proportionately higher than many of their white peers in the area.

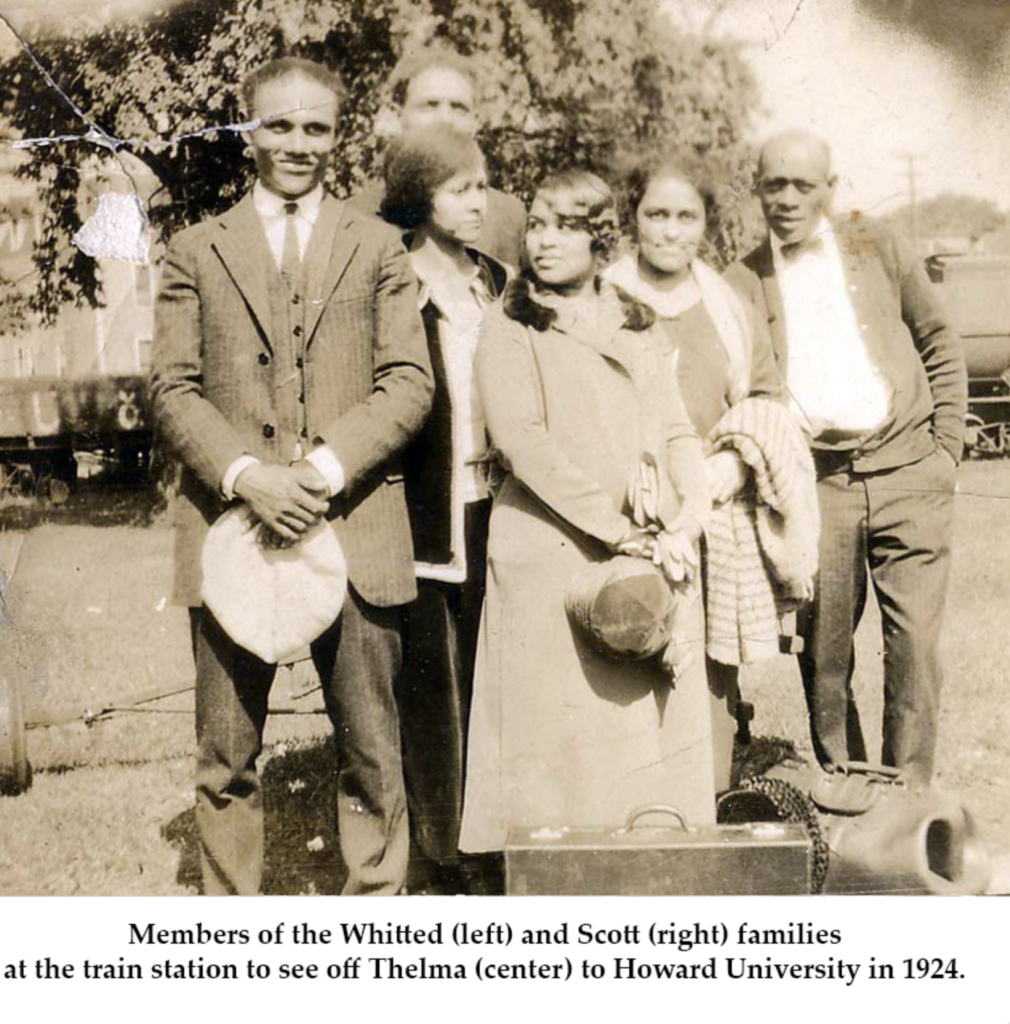

Among others, Roy Scott’s daughter Thelma, for example, journeyed after graduating from Culver High School to Howard University in Washington, D.C., a historically black college, where she met and married Morsell “Bob” Hodges, a black man earning his master’s degree in German. She returned with her husband to Culver and raised a family in the area, rising to prominence as an antiques expert and dealer and in local politics.

Charles and Lela Dickerson’s children included a son who became an accomplished graphic artist in New York City and children in professional roles in the aviation and public relations fields.

Jim Harper, who with his wife Ina lives in Culver today (having returned after retirement in Chicago), earned his degree as one of the few black students at the time to attend North Central College in Naperville, Illinois. Harper has been an active and revered member of the Culver community in recent decades, particularly with the local Lions Club, and also in gathering and sharing the story of Culver’s black community, and his positive experiences growing up here.

“I never considered myself pigeonholed because of my color,” Harper told a local audience in a 2013 event at the Culver Public Library. “Some others did, maybe, but I didn’t. I have always been a Culverite. I used to tell people, ‘I’m from a town where you were good until you proved yourself otherwise.’”

The once-flourishing black community of the town of Culver dwindled as Culver Military Academy shifted from waiter service to cafeteria-style dining in the late 1950s, and as employment trends finally moved away from race as a determinant nationwide. Clara Rollins’ 1906 prediction of improvements in race relations was thankfully coming true, but that also meant employment was opening up across the U.S., and Culver was losing its status as a place unusually suited to provide employment and a safe, respectful living environment for African Americans.

The 1950s also saw developments on or near two small lakes south of Culver, King Lake and Langenbaum Lake, originally aimed at creating resort experiences for African Americans from the Chicago area. Neither came to full fruition but they did foster new, rural black communities near the convergence of Fulton, Pulaski and Starke counties, though outside the town of Culver proper.

The year 1960 saw an entry in one of the Culver Citizen newspaper’s regular columns that was perhaps a sign of the times. “In the Colored Circles,” as an indication of the unusual level of integration Culver saw at the time, regularly documented the comings and goings of the town’s black residents, much as similar columns reported on the social lives of residents of Burr Oak, Delong, Hibbard, and other small, nearby areas.

The very last appearance of the column that had, by then, become simply “Colored Circles,” was written by Mrs. Nellie Jackson in 1960. Whether she knew hers was the last in a series of such reports dating back some 50 years, Jackson’s closing words that week, after detailing the Dickerson family’s efforts in driving many snowbound congregants to Rollins Chapel the previous week, seem to allude to the presence of the column itself: “We, being patrons of our only weekly paper, thank you for cordial treatment.”

Comments 3

Great article on Blacks and the Culver Community. Jeff Kenney is the Best!

Thanks for doing this.

Don Freese

I grew up in Culver and knew Mr Scott and his wife and their family well. Mr Scott was a good friend to me.

Great article, Jeff. Thanks for remembering these influential folks in the community and their uniquely American stories.