Two World War II Veterans of Johnson County Recall Incredible Stories

Photographer / Amy Payne

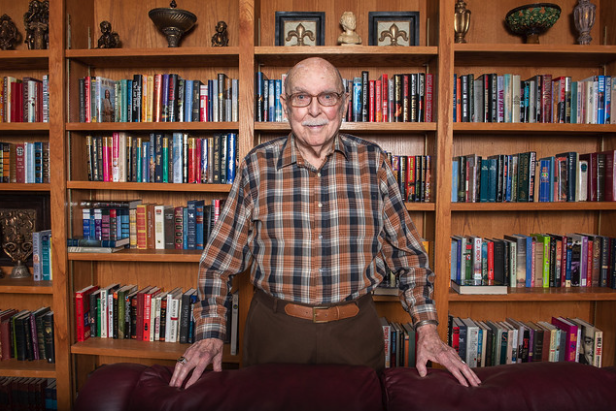

Born in Indianapolis in 1922, Walter Johnes joined the Army as a 21-year-old in mid-1943, assigned first to Fort Benjamin Harrison, a U.S. Army post that was located northeast of Indianapolis.

“The Army decided that everyone should have some kind of training so they sent me to Camp Blanding in Starke, Florida,” Johnes says. There he joined an intelligence program. “I was going to head to the College of William and Mary in Virginia, but they were losing a lot of people in the war so they sent me to Basic Training.”

Johnes was put in the rifle company at Camp Blanding and remained in Basic Training from September 1943 until February 1944. When he arrived overseas in New Guinea, he was scheduled to go to the 8th Army as a rifleman, training to go to the Philippines. One day he was called to the office.

“We want you to take nine men over to Port Moresby,” he was told. “From there you go to Brisbane, Australia, where you’ll be assigned to General [Douglas] MacArthur.”

Johnes was assigned to the paper mill.

“It was all paperwork as we kept track of all the units who were out in the field,” says Johnes, who handled top-secret materials as there were no computers at the time.

Johnes served in Tokyo, New Guinea, Manila, Okinawa and Yokohama.

The condition on the ground in some cities was incomprehensible. In Manila, for instance, there were still dead bodies in the buildings when Johnes arrived.

“You had to learn to breathe,” he says. “And the civilians were starving. We had a garbage can outside of our mess hall and Japanese civilians would line up for half a block to eat from it.”

Sadly, Johnes had friends and acquaintances who perished in the war, as did his brother, who got killed in the Battle of the Bulge.

Johnes recalls stories from the war that sound like they came straight from a soap opera script. For instance, there was a soldier who had an ill-fated love affair while he was serving overseas.

“One fella fell in love with a Japanese girl. The only trouble was he was married back home,” Johnes says. “He cried his eyes out [when he left her.]”

In Manila, a friend of Johnes’ was suffering from brain fatigue so he was sent to New Guinea to rest.

“The first night he was there, a Japanese plane came over and dropped a bomb and he was killed,” Johnes says.

As for his own crazy stories, when he was in the Philippines, he recalls drinking milk from raw coconuts and getting sick as a dog. He also had to take tablets to keep from contracting malaria. And then there were the bugs.

“One night I was sleeping with my mosquito netting down and something bit me,” Johnes recalls.

Inside his bed was a big black and yellow bug that looked like a caterpillar. Johnes’ extremities started swelling instantaneously so he ran to the medical tent.

“I was yelling, but the medic didn’t wake up so I turned his bed over,” Johnes says. Ultimately, he was told not to worry about it. But during the war, worry came with the territory as death surrounded him regularly. Men died from malaria, poisoning, bombs and war wounds.

Johnes was relieved to not lose his life, though he did lose his hair.

“I had a full head of curly hair when I left and when I returned, I was completely bald,” Johnes says.

During the two and a half years he served, Johnes corresponded frequently with family.

“I wrote letters. Boy, did I write letters. It was good therapy for me,” he says. “I had a big family so I wrote to everybody — my mom, sisters, cousins. I wrote every day to my wife.”

He let her know where he was through code by writing a single letter where her middle initial would go on the envelope. For instance, “A” stood for Australia or “P” for the Philippines.

Three years ago, on Johnes’ 94th birthday, he participated in the Indy Honor Flight where he flew to Washington, D.C. to visit the WWII and several other memorials. At the Arlington Cemetery, he was invited to put the wreath on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Though he declined due to mobility issues, he says it was an honor to be asked.

Johnes, who turned 97 last month, boasts that he doesn’t feel a day over 93 and has his eyes on the big 1-0-0.

“I read the obituaries today and saw a woman who lived to be 107. I thought, ‘Shoot. I can do that,’” says Johnes, who currently resides in Perry Township at an assisted living facility. “I quit smoking in 1960. My lungs are clear as a bell. I don’t feel one bit sick.”

In December 1945, Robert Bruce Phillips got notice in the mail that he had been drafted into the Army. He was a high school senior living in Eaton, Indiana, a town north of Muncie, when he and four of his classmates received the same letter from the President of the United States.

“That was a shock,” Phillips says. “None of us were expecting such news in the middle of our senior year.”

In May 1945, the young men boarded a bus to Camp Atterbury in south-central Indiana and were sworn into the Army. Phillips was then shipped to Camp Polk in Louisiana.

“We took Basic in the swamps with the snakes and alligators,” says Phillips, who was put on security duty with the atomic energy commission, a job in which he received FBI clearance.

“We took Basic in the swamps with the snakes and alligators,” says Phillips, who was put on security duty with the atomic energy commission, a job in which he received FBI clearance.

“I remember going home on a three-day pass,” Phillips says. “I went into a drug store and a friend of mine wanted to know what kind of trouble I was in. I said, ‘None. Why?’ He said, ‘Because the FBI has been in to check on you four times!’”

Phillips spent the majority of his three-year service in the sands of Arizona and New Mexico because atomic energy information was buried in the tunnels in the desert.

The lessons he learned during his service he still carries with him today —mainly, respect for fellow servicemen and the importance of protecting and standing up for one another. Now 91 (he’ll be 92 on Christmas Eve), Phillips is pleased that both of his grandsons are currently at Basic Training for the U.S. Marine Corps.

“I’m proud as can be,” says Phillips, a resident of Demaree Crossing, an assisted living facility in Center Grove/Greenwood.

He’s also immensely honored to be an American.

“Anytime the anthem is played,” he says, “my heart beats with pride.”