Mark Twain once advised people to “buy land, they aren’t making it anymore.” These days, that advice is often narrowed to waterfront property. But that’s not only incorrect as a quotation, it’s also untrue. New waterfront land is occasionally made. The forward thinkers of Anderson, Indiana, are considering a proposal to make a good bit of it. In exchange, they’re willing to give up a portion of Anderson itself.

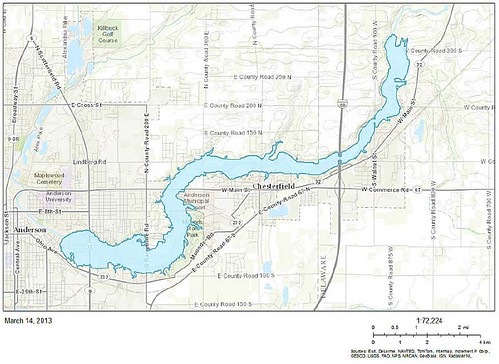

According to an article in the Herald Bulletin of March 14, 2013, written by Stuart Hirsch, the proposed Mounds Lake Reservoir — to be created by damming the White River — would be seven miles long and cover 2,100 acres (Geist covers 1,900 acres). The estimated cost on March 14 was $300 million to $350 million, though that estimate had risen to $400 million by the time the Republic of Columbus, Indiana, ran an Associated Press follow-up on the reservoir proposal on May 10.

Those millions are one way of expressing the cost of Mounds Lake. Another way is the percentage of Anderson’s land and infrastructure the lake would cover. According to the Herald Bulletin article, approximately “400 homes” and “several thousand feet of retail space” will have to be sacrificed. The latter includes Mounds Mall, not a big mall by Indianapolis standards, but one of the first enclosed malls in Indiana, complete with food court and multiplex. (Chesterfield and Daleville, two smaller communities, will also be affected.)

The construction of Geist Reservoir in the early 1940s required sacrifices, too, including a crossroads town called Germantown, whose footings still snag the occasional fishing line. But Germantown didn’t apply for inundation. Its movers and shakers, if it had any, didn’t donate money for feasibility studies, as Anderson’s currently are. Geist was the brainchild of Clarence Geist, owner of a water company in the then distant city of Indianapolis. In contrast, the Mounds Lake idea is homegrown. It originated with Quinn Ricker, President and CEO of the Ricker Oil Company, during a Leadership Academy of Madison County class. It has been shepherded since by the Madison County Corporation for Economic Development.

Anderson has been a place of starts and stops. It had to be incorporated as a town three times in the early nineteenth century before the designation stuck. Later, the discovery of natural gas led to a period of prosperity and growth and then to another setback when the gas ran out. The city’s next source of prosperity was the automobile industry, but eventually that ran out, too. From a peak of 70,000 in 1970, the population has dropped to 56,000. The city is ready for the next new thing. The next wave.

This time, it might literally be a wave. Or rather many waves sent out by many recreational users of the proposed Mounds Lake. And unseen waves passing through pipelines to still-growing cities like Indianapolis. As Quinn Ricker described his proposal to the Herald Bulletin, “It’s not incremental, it’s transformational.” One might almost say it’s biblical. It’s the kind of idea God had when he told Noah to build an ark, the notion that wiping the land clean — of multiplexes and strip malls — might really be the way forward.

Would Mark Twain be amazed by all this? Probably not. Though he died around the time Clarence Geist was proposing his lake, Twain had a pretty good handle on the modern world. In addition to the investment advice cited above, he once said, “Apparently, there is nothing that cannot happen today.”