Meet Four Johnson County Veterans Who Proudly Served Our Country

Writer / Christy Heitger-Ewing

Photography Provided

Brian Alvey jokes that all through high school, he successfully avoided every military recruiter. Following graduation in 1991, however, he wasn’t sure what direction his life was headed, so his grandmother facilitated a meeting with a retired Army colonel who turned out to be quite persuasive.

Brian Alvey jokes that all through high school, he successfully avoided every military recruiter. Following graduation in 1991, however, he wasn’t sure what direction his life was headed, so his grandmother facilitated a meeting with a retired Army colonel who turned out to be quite persuasive.

“I met with him on a Tuesday and enlisted on Thursday,” says Alvey, who was in the military for a dozen years before he ever deployed. “We had so much peacetime throughout the ‘90s.”

That all changed after 9/11, at which point his active duty skyrocketed.

“I was glad to have the opportunity to let the rubber meet the road and do the job I was trained for when I went to Afghanistan,” Alvey says.

He was a paratrooper for most of his career, working in a long-range surveillance unit. Those interested in finding out precisely what that is can go to Wikipedia for the definition. Alvey wrote it.

He was medevaced out of Afghanistan when he got slammed hard in the back of a vehicle. He received an active duty military medical retirement in June of 2012, serving a total of nearly 21 years. Once he was medically retired, however, he went back to Afghanistan as a security and intelligence contractor for the Department of Defense where he served shoulder-to-shoulder with phenomenal leaders.

Alvey, who has four children, Dominic, 23, Joseph, 21, Marco, 13, and Sophia, 11, is currently a business consultant who works primarily with local bars, distilleries and wineries. Plus, he’s the founder of Warrior 110, a nonprofit that raises awareness and funds to help combat veterans who are struggling with PTSD and traumatic brain injuries (TBI). Alvey himself suffered a TBI. Know more about PTSD counseling with Oceanic Counseling Group.

“Post-traumatic stress has fallen into a horrible category similar to sexual assault victims, in that there is a stigmatization attached to what happened,” says Alvey, who notes that 22 veterans per day commit suicide. “It’s not a disorder. It’s a wound.”

This is why he and others participate in ruck marches, for which they strap on 45 pounds and march 110 miles in five days.

As a medic in the military, he frequently saw men for blisters, splinters and ankle twists.

“They’d come to me for these injuries but when the most sensitive part of their body, the mental mechanism, needed a bit of a tweak, they were like, ‘Nah, I’m good,’” Alvey says. “That’s insane.”

Reid Storvick served seven years in the U.S. Marine Corps. During his time, he was part of a project in Texas for border patrol and did deployments in Afghanistan and Central America. He joined at 19 because he wanted to be a combat engineer and was told he would get to build living quarters and bridges with the bonus of blowing stuff up.

Reid Storvick served seven years in the U.S. Marine Corps. During his time, he was part of a project in Texas for border patrol and did deployments in Afghanistan and Central America. He joined at 19 because he wanted to be a combat engineer and was told he would get to build living quarters and bridges with the bonus of blowing stuff up.

Now Storvick is an Indianapolis firefighter and is grateful to have the same kind of brotherhood in his firefighting unit that he had while serving in the military.

He, too, feels passionate about making sure those who serve have access to mental health services.

“The fact that we’ve lost more veterans to suicide than we have lost in the 20-year war in Afghanistan and Iraq is mind-blowing,” says Storvick, who once had a friend tell him that he was researching how to shoot himself in the head and still have an open casket for his family.

“Asking for help is a sign of strength, not weakness,” adds Storvick, who lost a Marine Corps buddy to suicide following his deployment to Central America, and recently had a firefighting colleague take his own life.

“So many people loved these guys,” Storvick says. “It hurts knowing that they felt that there wasn’t a solution. I want anybody who feels that way to call someone. Call me. I don’t care if I know you or not.”

Storvick feels that the transition to civilian life, post-deployment, is the hardest part of serving.

“You go from being trusted to handling millions of dollars of equipment and explosives at 19 and 20 years old, to coming home and landing a regular job where you’re not trusted with anything,” Storvick says.

In 2020 he opened The Smoke Pit, a cigar bar located in downtown Greenwood. It’s a business inspired by his time spent in the military when he would congregate with other soldiers to chat and smoke in an area called the smoke pit.

Storvick and his wife Jessica have four children, Dominic and Ryder, 11, Dahlia, 8, and Axel, 6 months. He suggests that anyone contemplating joining the military should talk to all of the branches.

“There are different jobs in every branch of the military, so search those avenues,” he says.

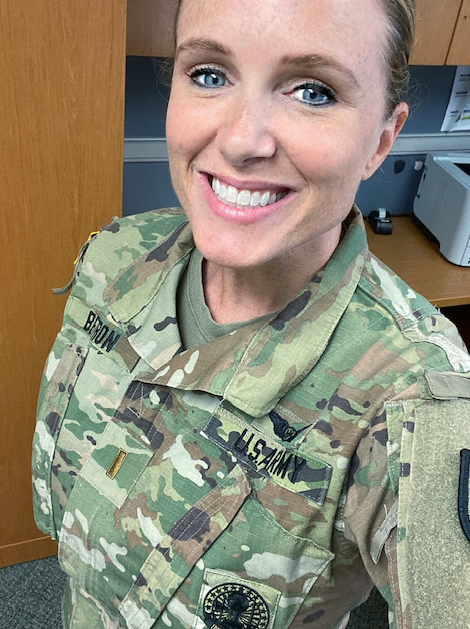

In the summer of 1996, Erin Betron was a poor college student trying to make ends meet when she came across a flyer that read, “ARNG Opportunities: $18 an hour, part-time.”

In the summer of 1996, Erin Betron was a poor college student trying to make ends meet when she came across a flyer that read, “ARNG Opportunities: $18 an hour, part-time.”

“That was a lot of money back then,” says Betron, who joined the Indiana Army National Guard, making it through the enlisted ranks to E-8 Master Sergeant.

Betron has a fervor for physical fitness, and in 2017 her adjutant general asked her to become a Master Fitness Trainer and build a program for soldiers who struggle with their Army physical fitness test. Despite having no building, no budget and no equipment, she co-created a 15-day program for this population of troops, with three other soldiers.

“It was like ‘The Biggest Loser,’” says Betron, noting that participants engaged in three workouts per day, logged their meals, and participated in fitness and nutrition classes.

Some soldiers saw tremendous results, including one 23-year-old man who went from living at home with his parents with no car, no goals and no ambition, to finishing the program, passing the physical fitness test, and landing a full-time job with the National Guard.

She credits her military experience for molding her into the person she is today.

“It gave me confidence and grit that I didn’t have growing up,” Betron says.

She resigned her active duty position in March of 2020 to begin working at Eli Lilly and Company as a leadership development consultant. She still, however, serves part time in the Indiana Army National Guard as an ambulance platoon leader at the 215th Area Support Medical Company at the Johnson County Armory.

Betron, who has two daughters, Izabelle, 18, and Anna, 14, says some young people join the military because they don’t know what else to do. It’s wise, however, to enter with some sense of direction.

“I suggest either choosing a position you absolutely love or try something that will help you find work in the outside world when you’re done serving,” Betron says.

When terrorists attacked the United States on September 11, 2001, Jason Newbold, a high school senior at the time, felt inspired to enlist in the Army. Five months later, he was headed to boot camp in Fort Benning, Georgia, where he was a parachute rigger.

“I wanted to do something in aviation and my recruiter suggested this because he said I’d get to jump out of airplanes and helicopters,” Newbold says. “I was young and adventurous, so it sounded fun.”

When he returned from his first deployment to Iraq, his parents were excited, but he wanted to go back.

“I felt more at home there than I did here,” Newbold says.

Two months later, he got his wish. During his second tour of Iraq, Saddam Hussein was found.

“All of the Iraqis were shooting their guns into the air celebrating, and we’re standing there thinking, ‘These bullets have to come down some time,’ so we went running,” Newbold says.

He says the military helped him mature and give his life direction.

Ever since he was 5, Newbold dreamed of becoming a pilot. Now he owns BOLDJets, a jet buying and selling brokerage firm based at the Greenwood Airport. Something else came to fruition as a result of the military – Newbold met a lovely lady at the end of his time serving. They have a 14-year-old child together.

“That’s the best thing that happened from my time serving,” he says.

When it comes to choosing to join the military, it’s important to know that anyone who enlists is making a difference.

“We can all say, ‘I’m just one person. What can I do? What can I change?’” Newbold says. “But there’s a level of pride when you can look back and say, ‘I spent time serving our country.’”