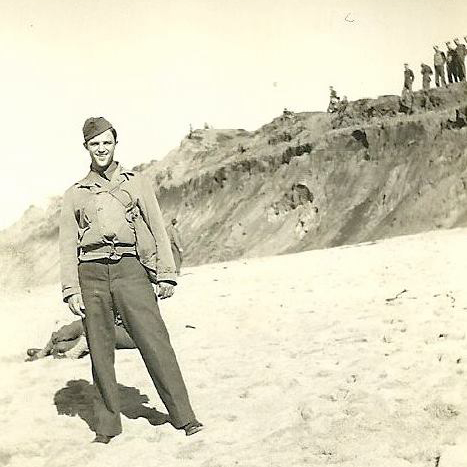

My father, Stephen Carlos Matheis, was inducted into the service on September 15, 1941, a few months before the United States entered World War II. According to his draft registration, he worked at Wood Mosaic, a factory close to the L&N (Louisville and Nashville) Railroad yards in Highland Park, a working-class neighborhood in South Louisville that was demolished in the 1990s to make room for airport expansion. His father, Stephen Louis Matheis, also worked there and had been for more than 10 years. He had worked for L&N up until 1929. He was part of a strike that year, not long before the Great Depression hit in October. The strikers were fired. A few months later, he lost his house. A few years later his marriage ended.

Having been accepted for active military service, my father was immediately sent to Fort Thomas, Kentucky, to await orders. He was shortly assigned to a New York National Guard unit which had been federalized into the regular Army to become the 27th Army Division. It was supplemented with draftees mostly from Kentucky and Indiana. During the fall of 1941 and the winter of 1942, the division trained in Alabama and Texas. It became the first Army division to leave the United States for the Pacific Theater after Pearl Harbor, departing from San Francisco in March of 1942. My father would not return to the United States until October of 1945.

The division went directly to Hawaii. It remained there on garrison duty, awaiting further orders for 18 months. It then became one of the few Army divisions attached to the island-hopping campaign through the Central Pacific with the ultimate goal of attacking the Japanese home islands. The battles of this campaign were chiefly fought by the United States Marines. My father was in the 165th regiment of the 27th Infantry. He was in Company H, a heavy weapons company, and assigned to water-cooled machine guns. Gradually he was promoted to staff sergeant.

His first battlefield action was in November of 1943 when the 165th regiment was detached from the 27th Infantry Division to capture the atoll of Makin, which contained a small Japanese defensive garrison. While the 165th was accomplishing its objective, a Marine division was to take nearby Tarawa, where there was a much more formidable Japanese force. Tarawa became the biggest island battle of the war to that point, ending in a resounding Marine triumph. The 165th was expected to capture Makin in one day but took three. The green troops faced much stiffer-than-expected resistance from the Japanese.

In the Pacific Island battles of World War II, the Japanese soldiers were expected to fight to their last breath, to die for the emperor. They resisted fiercely until the very end of every island battle. Surrender was not an option. After the first few battles, the Japanese learned quickly they could not successfully defend the invasion of beaches because of superior American firepower. Their strategy became one of attrition. They would wait for the Americans in the island interior and try to kill as many of them as possible. Battles usually became slow, grinding, bloody affairs. Almost all island battles ended with a banzai attack in which the remaining Japanese forces would make a suicidal rush on American lines at night.

After Makin, the 165th regiment rejoined its division in Hawaii. The 27th Infantry began preparing for the invasion of Saipan. The island of Saipan had been a Japanese possession before the war. The islanders considered themselves Japanese citizens. The battle would be the first fought on what was essentially Japanese soil. For this reason, even stiffer resistance was expected.

On June 15, 1944, the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions established a beachhead on the western shore of Saipan. The 27th Infantry was then brought ashore to become the middle division of a three-division front that would advance across the island. The Marines and the Army were trained differently. Marines were trained to take their objectives at all costs. Army troops were trained to keep casualties as low as possible while advancing. This difference in training became quickly apparent at Saipan. The 27th Infantry could not keep up with the Marine divisions, causing the line to form a “U” shape and exposing the Marines to flank counterattacks. The Marine general in overall charge of the invasion force replaced the 27th’s commanding general. His replacement was able to get the division to advance faster to straighten out the American line of attack.

By early July, the American forces had surrounded the Japanese defense forces in the northeastern corner of the island. The Japanese staged their banzai attack. After that was defeated, the island was captured. The Battle of Saipan was notorious for what happened as it ended. As mentioned earlier, the island’s natives were Japanese citizens before the war. During the battle, the Japanese soldiers had spread rumors about the atrocities the Americans would commit if the island fell. Out of fear, more than 1,000 islanders committed suicide, mainly by jumping off cliffs into the sea below. About 3,200 Americans and 25,000 Japanese soldiers died at the Battle of Saipan.

After the Battle of Saipan, the 27th Infantry was sent to Espiritu Santo, a small French-controlled island off the coast of Australia, to train for the Battle of Okinawa, which would become the climactic battle of World War II. The battle began on April 1, Easter Sunday, as my father once told me. The 27th Infantry was once again brought on shore after a beachhead was established, and was inserted into the right side of the line that would advance on the southern half of the island where most of the Japanese resistance was located. After difficult fighting throughout the month of April, the division was taken out of the frontlines and sent to garrison the mostly pacified northern half of the island. Japanese resistance on Okinawa ended at the end of June. Over 12,000 Americans had died in the battle, along with over 94,000 Japanese soldiers and thousands of civilians.

My father’s division was slated for the planned invasion of Japan itself. One million American casualties were anticipated from the invasion. It, of course, never took place. The Japanese surrender following the atomic bomb attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. My father returned to the states in October of 1945 after three and a half years overseas. He was honorably discharged on October 15, 1945, from Camp Atterbury, Indiana.

But the war left its mark on him for the rest of his life. His memories of battle, atrocities (on both sides), and friends dying in the night haunted his dreams. He had what today would be called post-traumatic stress syndrome. More than 20 years after the war, he spent three weeks in a mental hospital. Although he did not make the ultimate sacrifice, like the more than 400,000 Americans who did in World War II, he still paid a heavy price, like untold thousands of soldiers across all the wars this country has fought.