Photos courtesy of University of Louisville Archives & Special Collections

St. Matthews today has a strong economic base of retail businesses, automobile dealerships, dining establishments, and healthcare facilities, located around its many neighborhoods and subdivisions.

St. Matthews today has a strong economic base of retail businesses, automobile dealerships, dining establishments, and healthcare facilities, located around its many neighborhoods and subdivisions.

But our community’s past is rooted in agriculture, and the roots run deep, dating back to the settlement era.

The area south of the Falls of the Ohio River, what would become Jefferson County, must have been a paradise in the 18th century.

There was numerous springs, and local streams were rich in fish and mussels. Much of the land was level, soils were fertile and wildlife was abundant. In the fall wetlands were filled with migrating waterfowl, and the forested uplands supported eastern elk, black bears, wild turkeys, and white-tailed deer.

These were prime hunting grounds, claimed by both the Shawnee and Iroquois.

Col. James John Floyd, of Virginia, was Jefferson county’s first landowner and early settler.

As deputy surveyor of Fincastle County, Floyd had surveyed the area in 1774 and had his pick of the most geographically desirable land. He claimed two 1,000 acre parcels in what is now the heart of St. Matthews.

In November, 1779, he moved his family here from Amherst County, Virginia. He built a cabin, and later a fort, called Floyd’s Station, on what is now Breckinridge Lane. Floyd’s Station was one of six stations, fortified stockades, built on the Middle Fork of Beargrass Creek, which flows through the center of Jefferson County.

By the early 19th century some of the large parcels of land associated with the six pioneer stations, and other lands awarded to veterans for their service in the Revolutionary War, were developed into plantations. The major crops were tobacco, hemp, corn, wheat and livestock, primarily horses.

Strategically located about six miles east of downtown Louisville, St. Matthews sits astride an old buffalo trace. By 1820 this pioneer road, that connected the Falls of the Ohio with the seat of state government in Frankfort and the Bluegrass Region beyond, was known as the Shelbyville Turnpike, now US 60.

Initial development, known as Gilman’s Point beginning in the 1840s, was around its intersection with Westport Road (Ky 1447). Other important roads converge here too — Breckinridge Lane, Lexington Road, and Chenoweth Lane.

The coming of the railroad, linking Louisville to Frankfort in 1851, and later, an interurban spur line about 1910 that came through St. Matthews, had a big impact on our community.

An influx of German and Swiss immigrants in the late 1850s, and later, immigrants from Ireland, brought a change of what was being grown here and how it was being sold, as subsistence gardening evolved into commercial vegetable production. Local produce, first sold in our community’s many neighborhood grocery and general stores, was later a cash crop shipped to distant markets.

An influx of German and Swiss immigrants in the late 1850s, and later, immigrants from Ireland, brought a change of what was being grown here and how it was being sold, as subsistence gardening evolved into commercial vegetable production. Local produce, first sold in our community’s many neighborhood grocery and general stores, was later a cash crop shipped to distant markets.

The railroad helped launch an agriculture-based economy, and was the major reason why our crossroads community became an important distribution center.

Market gardeners began to cultivate plots throughout the fertile and well-watered Beargrass Creek basin in and around St. Matthews, and when their crops were harvested, the railroad transported them to markets in Louisville and beyond.

St. Matthews became known as “the garden of the state” for the quality produce grown here, and its distribution status.

Some farmers diversified. Nanz, Neuner & Company was the largest horticultural operation in the 1870s, with a nursery complex of 30 greenhouses along what is now Breckinridge Lane. Plants, seeds, flowers and vegetables were available on site or could be purchased at the company’s market store downtown.

At the turn of the 20th century, many of our city’s most prominent citizens were farmers or market gardeners.

The local food economy really took off during the first decade of the new century when farmers in the vicinity of St. Matthews began to concentrate on raising potatoes and onions as cash crops, as demand for these staples grew.

At the center of St. Matthews, the triangle intersection of Shelbyville Road, Chenoweth Lane and Westport Road, was an open space with a scale where produce and other agricultural products in wagons were weighed.

The interurban spur line that came from Louisville over Shelbyville Road terminated at Westport Road, to service the St. Matthews Ice and Cold Storage and later the St. Matthews Produce Exchange, a farmer cooperative, built on St. Matthews Avenue.

The St. Matthews Ice and Cold Storage opened in 1909. The facility made and sold ice, and offered local farmers a place to store and refrigerate produce, fruits, meats and other perishables, prior to their sale.

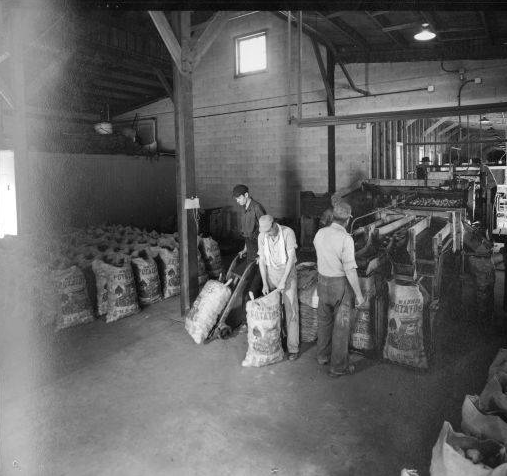

The cooperative, incorporated in 1910, was formed to find markets for, and negotiate the sale price of local produce, primarily potatoes. Farmers brought their crops to the scales to be weighed, then the potatoes were unloaded at the warehouse and graded.

Reportedly, in their first year of business, the St. Matthews Produce Exchange shipped 250 railway carloads of potatoes, netting farmers 60 cents per 100 pounds. Not only did the exchange sell potatoes and other locally-produced vegetables, but it purchased items farmers needed, such as fertilizer and twine in bulk quantities.

So many potatoes were grown here that St. Matthews became a major center in the country for this crop. By 1920, more than 13 million pounds were sold, with about 20 percent trucked to Louisville and the remainder shipped by rail to distant markets.

A 1922 article in The Louisville Herald proclaimed that “St. Matthews is the second largest onion and potato shipping point in the United States…(that) last year, during the months of July and August, the St, Matthews Produced Exchange sold more than 200,000 barrels of onions and potatoes. The priced obtained for the lot was about $1,000,000.”

A 1925 article in the Christian Science Monitor pointed out that Jefferson County is “one of the greatest potato shipping centers in the country…a leader in second-crop potatoes. Its climate and soil permitted two crops of tubers on the same land, in the same year.”

By 1925 the St. Matthews Produce Exchange had 400 members and shipped 1,200 train car loads of potatoes and onions annually.

The area began changing in the mid-20th century. Gradually the farms were subdivided and developed with residential housing, and shopping developments. The St. Matthews Produce Exchange ceased operation in 1954.

But our community’s agricultural heritage continues anew each Saturday that the St. Matthews Farmers Market is open.

Farmers from the surrounding region converge on the campus of the Beargrass Christian Church, along our city’s main thoroughfare, to sell local vegetables, fruits, meats, breads, dairy products, flowers, landscaping plants and handmade arts and crafts.

The layout of the tents creates a festive L-shaped market, with plenty of room for shoppers to circulate and socialize. Live music and the smell of coffee and breakfast foods fill the air.

Our proud past lives on as we gather to celebrate the roots of agriculture that run deep in our community’s history.

Comments 4

When did they stop using the train station & Ice House on Westport Road near Chenoweth Lane and White Cstle?