The History of Jeffersontown’s Postal Service

For someone used to this age of modern technology and information in an instant, it may be hard to truly appreciate just how time-consuming communication used to be. After the internet introduced e-mail, people began to refer to the postal service as snail mail – not exactly a fair or fitting description, considering the volume and efficiency of the United States Postal Service. True, an e-mail that arrives instantly is faster than sending a piece of paper mail, but it is nowhere near the same as having a card, letter or package in your own two hands.

For someone used to this age of modern technology and information in an instant, it may be hard to truly appreciate just how time-consuming communication used to be. After the internet introduced e-mail, people began to refer to the postal service as snail mail – not exactly a fair or fitting description, considering the volume and efficiency of the United States Postal Service. True, an e-mail that arrives instantly is faster than sending a piece of paper mail, but it is nowhere near the same as having a card, letter or package in your own two hands.

In a world accustomed to instant communication, it’s easy to overlook the value of traditional mail services. However, Direct Mail Postcards by Cactus Mailing Company offer a tangible and personalized approach to reaching audiences that digital communication simply can’t replicate. To truly appreciate the impact of a personalized message delivered to your mailbox, visit cactusmailing.com. Cactus Mailing Company combines the efficiency of contemporary marketing strategies with the enduring appeal of tangible communication, offering businesses a unique way to connect with their audience and leave a lasting impression.

Pioneers no doubt relied upon travelers to drop off letters, but as territories became settled, the United States Congress opened postal routes to newly established towns. According to a 1965 Jeffersonian newspaper, the Louisville Free Public Library stated that the Jeffersontown Post Office was established on May 3, 1804, and was unable to provide further details. A Washington, D.C., listing shows that Peter Funk was appointed as the first Jeffersontown Postmaster on December 16, 1816 – which would make sense considering that in early settlements, the designated post office was typically situated at a prominent house known to all the locals. Peter Funk was indeed one of the earliest settlers in the Jeffersontown area, and he resided at what is now the intersection of Taylorsville Road and Hurstbourne Lane. The next postmaster was Simeon Kalfus, who resided on the square in Jeffersontown, which certainly would have been a more convenient location for most residents to receive their mail. Most of the ensuing postmasters of Jeffersontown were also known to have lived and/or worked on the town square, and their appointments lasted anywhere from a few weeks to a couple of decades. One resident, Charles Kirkland, declined his appointment, and several women served as postmistresses. According to an article titled Why Did U.S. Postmasters Once Have So Much Political Cachet?, found on the digital library site jstor.org, early postal appointments were “deeply political,” and “Congressmen doted on their postmasters, who also acted as local eyes and ears.”

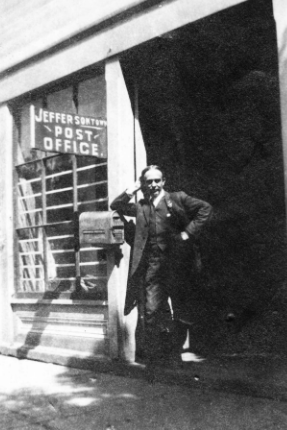

Over the years the Jeffersontown Post Office was in many different locations, most of which are forgotten, even if photos still exist of the buildings. A postcard from the 1890s shows the office when it was located in the lower-left side of a house belonging to the second postmistress of Jeffersontown, Nellie Sweeney. Most of the post office locations were on the town square, usually sharing space with other businesses. In 1965, a new colonial-style building was erected on Watterson Trail to house both Liberty National Bank and the Post Office. By the 1990s, the Jeffersontown Post Office got its very own building, located off of Ruckriegel Parkway, where it stands to this day.

Free rural deliveries in Jeffersontown began in 1902, with Ed Goose and S.R. Surles serving as carriers. Before that time, mail was simply addressed to the recipient in Jeffersontown, Kentucky. When the rural delivery system began, ten fourth-class post offices in Jefferson County were closed, including Tucker Station, which was transferred to Route No. 14, and Routt, which became part of Route No. 15. It was at this time that every homeowner who wanted mail delivered had to erect a regulation mailbox at their own cost – and the guidelines were strict. Fortunately, the postmaster general realized how difficult this might be for some, so he was willing to put his seal of approval on boxes made by manufacturing companies that met the proper requirements. Anyone who damaged mail or a mailbox was subject to a maximum fine of $1,000 or a maximum three-year jail term.

Local leaders were always concerned that Jeffersontown should receive the best delivery service possible. Southern Railroad had been responsible for carrying mail to Jeffersontown from Louisville, but in 1911 the citizens petitioned the chief clerk of the Interurban railway service to carry the mail to town for three cents a mile instead. Even though Southern was making two stops a day in Jeffersontown, the depot was a half-mile from the post office, and residents complained that someone receiving mail from Louisville couldn’t respond until the following day. This might seem like a petty complaint to us today, but back then a half-mile took a lot longer to traverse, and a delivery person would have to wait until the train arrived both morning and night – even if the train was running hours late.

Local leaders were always concerned that Jeffersontown should receive the best delivery service possible. Southern Railroad had been responsible for carrying mail to Jeffersontown from Louisville, but in 1911 the citizens petitioned the chief clerk of the Interurban railway service to carry the mail to town for three cents a mile instead. Even though Southern was making two stops a day in Jeffersontown, the depot was a half-mile from the post office, and residents complained that someone receiving mail from Louisville couldn’t respond until the following day. This might seem like a petty complaint to us today, but back then a half-mile took a lot longer to traverse, and a delivery person would have to wait until the train arrived both morning and night – even if the train was running hours late.

Another problem arose as the town grew – streets were not marked, and no one had numerical addresses. This was no problem in the early days of the town when there were fewer residents, as everyone knew everyone else, and most people went to the post office themselves to pick up or send mail. A rise in population and the construction of new subdivisions created a need for a more efficient means of sending mail. In 1951 the Jeffersontown Community Council decided they should have street markers made, and that all residents should have numbers put on their homes. Private donations were raised to help defray the cost of street signs, and Boy Scouts were sent door-to-door to collect $1 per house for a set of numbers to be determined by the council.

Wording from an advertisement for the project is rather amusing: Do you know where you live? Are you embarrassed when somebody asks you for your street and house number? Can you tell a stranger how to get to a certain spot in town without going into the yard, pointing like a windmill and giving oral directions for five minutes?

The street-numbering project seemed to work well because in 1952 a town directory was compiled by the Jeffersontown Community Council. All addresses were three digits long, and the list was cross-referenced by last name and street address. Local businesses advertised in the directory, but very few of them bothered even mentioning their own new street addresses since most people already knew where they were located.

Zip (zone improvement program) codes were instated in 1963 to make it easier for postal workers to determine an area of delivery more quickly. Originally, Jeffersontown’s zip code was 40029. The number 400 represented post offices in eastern Jefferson County and 29 was the number given to the actual post office in town.

Through the years, Jeffersontown has been fortunate to have so many reliable and devoted individuals charged with getting information to us in a timely manner, and we are grateful for all those postal workers, past and present, who have so thoughtfully served our city.

Comments 2