A Woman’s Perspective

Writer / Beth Wilder

Photography Provided

Our colonial forefathers were of a brave and bold stock. By the late 1700s, most had already participated in the Revolutionary War for independence from British rule, and many still had the thirst for adventure in their veins. That, coupled with their war pensions and land grants, inspired a move to spread westward, even though no one was certain what they would encounter.

The men did not always move west on their own. Many a wife gathered her children, bade goodbye to the loved ones who raised her, and dutifully accompanied her husband into the unknown. While it took a certain fortitude to brave a trek into virgin territory, not all of these women were the hardy farm wives so often pictured as our pioneer forebears; quite often, these women were well-bred and educated, from well-to-do families. The journey itself had to have been arduous, especially for women born in such areas as Pennsylvania and Maryland, where cities had long been established, and relative safety was taken for granted.

Not all women willingly accompanied their husbands into the wilderness, however. In the late 1700s, Indian attacks were still occurring on settlers who were invading their territories, and that in itself would have been enough to cause a wife to forego the move westward. The first divorce obtained in the state of Kentucky was by Susannah Boyer Funk, who refused to move from Maryland with John Funk, who had inherited property in what would become Hardin County. It was no simple feat to obtain a divorce in those days; the reasons for the divorce had to be agreed upon by an act of the Kentucky General Assembly. Luckily for Susannah, they accepted her husband’s complaint that she “deserted him five years ago and lives in open adultery with another man in Maryland.” He also stated she refused to come to Kentucky in 1791. Their divorce was granted on July 3, 1798.

So, a woman of that era could put her foot down and stand up for herself, although it did practically take an act of Congress for that to be permitted. And yet, there are instances from Jeffersontown’s own past that not only shed light on how women’s rights were handled, but also the intelligence and caring involved in seeing to it that women received justice.

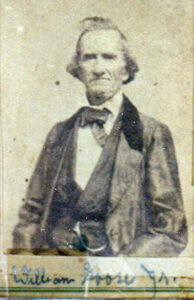

In 1791, a large influx of German families from York County, Pennsylvania, made their way into Jefferson County, Kentucky. Among them was William Goose Sr., who was a wagon maker, wheelwright and furniture maker (he also happened to be an ancestor of the award-winning jockey Roscoe Goose). He purchased 327 acres in the vicinity of Jeffersontown in 1797 and moved there with his family.

William Goose had married Catharine Yenowine around 1785, but about the time they made the move to Kentucky, they began having marital problems. Things built to a head in 1806, when Catharine was pregnant with their youngest child. William tried to attack Catharine with a broad axe, so she ran to the home of her nearest neighbor, Samuel Blankenbaker, for protection. Her father and brothers were notified of the incident, and when they arrived at the house, they found William sitting at a table reading a book, and he wanted to know why they were there at that time of the night.

Catharine was the daughter of Captain Johann Leonard Jenewein (later spelled Yenowine), who believed firmly that his children, males and females alike, should be educated. Catharine received as good an education as could be had in 1780s Pennsylvania, and she was nobody’s fool when it came to protecting her rights and those of her children. She relied on her brothers and neighbors to see her through, while she and William tried to make their marriage work. After the 1806 incident, however, even William himself was unsure if the marriage would last, so he deeded all of his property to two trustees to see to the maintenance of Catharine and his six children “during such time or years until the unhappy differences now subsisting between me and my wife are happily laid aside and compromised, and I and Catharine my wife can agree to live together.”

It did not work. In 1811 Catharine went to court to request a divorce and maintenance after almost 20 years of marriage. She testified that for the past 10 or 12 years he behaved poorly toward her, “but about five years ago he commenced a course of treatment toward me, so brutal, barbarous, dishuman as not only to render my situation too intolerable to bear but as to endanger my life…by his threats and abuse I was driven from the house of said William and remained upward of two years absent, obtaining the means of subsistence from my brothers and neighbors.”

William, for his part, testified that he never treated her brutally and claimed she deserted him.

William, for his part, testified that he never treated her brutally and claimed she deserted him.

In 1812 the court ordered William to pay $25 per quarter in alimony, and the next year the court took depositions from 17 people including five of Catharine’s brothers and sisters and three of her children. In July 1813 the court granted Catharine a divorce and two-thirds of William’s property.

Catharine never remarried, but William did. An 1824 deed for lot number 5 on the town square sheds further light on how women in Jeffersontown were treated.

William Goose Sr. ran his business from a building that sat on lot number 5, at the corner of what is now Watterson Trail and College Drive. On June 7, 1824, William and his second wife, Elizabeth, deeded the property to his son, William Goose Jr., for $150. Apparently, part of the deal was that William Goose Jr. would provide his father with “board, washing and lodging for life,” although that agreement was not mentioned in the actual deed. Elizabeth did not appear to be mentioned in that arrangement, and William Sr. died a few years later, perhaps leaving the widow Elizabeth without a place to live.

It is interesting to note that Elizabeth is included on the deed to begin with, but what is more interesting is what is mentioned in the last paragraph of the deed, which is an addendum written by the county clerk at the time, Worden Pope.

In it, Pope notes that William Goose Sr. and Elizabeth were both in his office and acknowledged what was agreed upon in the deed. He goes on to state, however, “I examined the said Elizabeth privily and apart from the said William her husband and having shewn and explained the said deed to her she declared of her own free will and consent signed sealed and delivered and acknowledged the said deed to be her act and deed without the persuasions threats or compulsion of her said husband…”

So, it appears that the county clerk thought that perhaps Elizabeth was signing away her rights to the property under duress, and offered her the chance, in private, to speak up, if that were the case. Pope duly noted Elizabeth told him “that she was willing the said deed should be recorded and did not wish to retract her said acknowledgements.” All this looks as if Pope had a genuine concern for Elizabeth’s well-being, and it reads as if he did not really believe she was being treated fairly, nor was she truly OK with the property being handed to Goose Jr., but he was obligated to record the deed anyway.

The stories of these two wives of William Goose Sr. show how tied women were to the restraints of colonial laws, yet they also show how much concern was expressed for their rights as human beings. A divorce was very difficult to obtain in those days, especially when it had to be approved first by the Kentucky General Assembly, then by the county court. Not only was Catharine’s divorce granted due to the unfortunate circumstance of her husband’s cruelty, but her educated nature, loving family and caring neighbors helped protect her and see her through a very trying time. That she was awarded upkeep and child support seems entirely fair to us now, but at the time she was probably lucky to get it, considering how many strangers to Catharine had to be consulted merely to obtain her divorce.

Sallie Cheatham Smith, a direct descendant of William Goose Sr. and Catharine Yenowine, credits a great deal of women’s rights in early Jeffersontown to the actions of Catharine. “They learned from other women at a specific time,” she says. “They had the ability to go before the court system and said, ‘This is what happened. I wish to be out of that marriage.’ And they followed through with that. She was a strong woman and I’m very proud of her, because there are others in the community, I’m sure, that she also helped in the times and province.“

Elizabeth’s story presents a picture of the concern others felt for a woman whose husband was domineering, to say the least. Considering how few rights women had, even during the later Victorian era, it is fascinating to see that women in little, rural, colonial-era Jeffersontown were viewed with respect, and looked after by their fellow citizens. That is something of which to be proud.

Considering how few rights women had, even during the later Victorian era, it is fascinating to see that women in little, rural, colonial-era Jeffersontown were viewed with respect, and looked after by their fellow citizens. That is something of which to be proud.