Writer / Jeff Kenney

Photography provided by Antiquarian and Historical Society of Culver

At some point, undoubtedly an older person has referred to getting something cold out of the “icebox,” though you may or may not have associated such an activity with a nearby lake or other body of water.

At some point, undoubtedly an older person has referred to getting something cold out of the “icebox,” though you may or may not have associated such an activity with a nearby lake or other body of water.

Harvesting ice was not only an integral part of everyday life for many, but also a financial and economic powerhouse. Doing so was common on lakes and ponds across Northern Indiana, but the ice boom on Lake Maxinkuckee was one of the most successful in the region and had its start in the early 1880s.

Maxinkuckee’s ice business was remarkable for the sheer magnitude of product – and employment – it generated. A cover story headline in The Marmont Herald newspaper declared, “Ice for Millions…Over Four Hundred Car Loads Cut Thus Far this Season (and not half of the ice houses filled yet…an industry that is a God-send to the laboring men in the winter).”

This claim was no exaggeration considering how many in Culver were farmers or manual laborers in those days, which meant winters could be economically tough. The 1895 article continues:

“The ice cut from Maxinkuckee Lake is of superior quality and brings a higher price in the market. During the harvesting of the ice, from two to three hundred men are employed, that is when running a full force, and it is not only a bonanza for the laboring men in this place, but scores of farmers have the opportunity to earn a little extra “change” which comes in handy, especially at this time of the year…from $1.00 to $1.50 per day is paid to the men, and when we say about $15,000 is left here every year, the outside world can readily see the magnitude of this mammoth industry.”

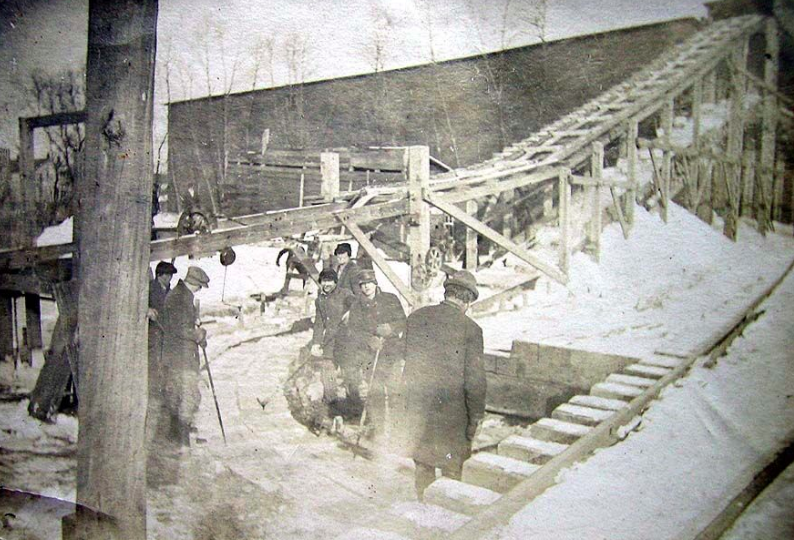

Ice harvesting on the lake took around two to three weeks each winter, with workers laboring through the night. Carbide lighting and a large, reflective sheet lit the ice “field” and house in those pre-electrical days.

Ice harvesting on the lake took around two to three weeks each winter, with workers laboring through the night. Carbide lighting and a large, reflective sheet lit the ice “field” and house in those pre-electrical days.

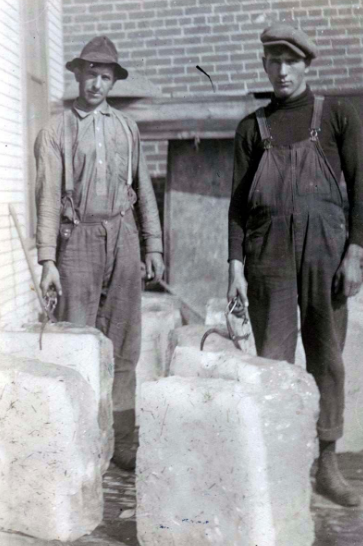

Ice had to be at least nine inches thick to be harvested, and the ice field extended out several hundred yards square from shore. Ice was scored in a checkerboard pattern using horses, and large blocks of ice were broken loose with pike poles. These were pushed along a channel to the waiting ice house.

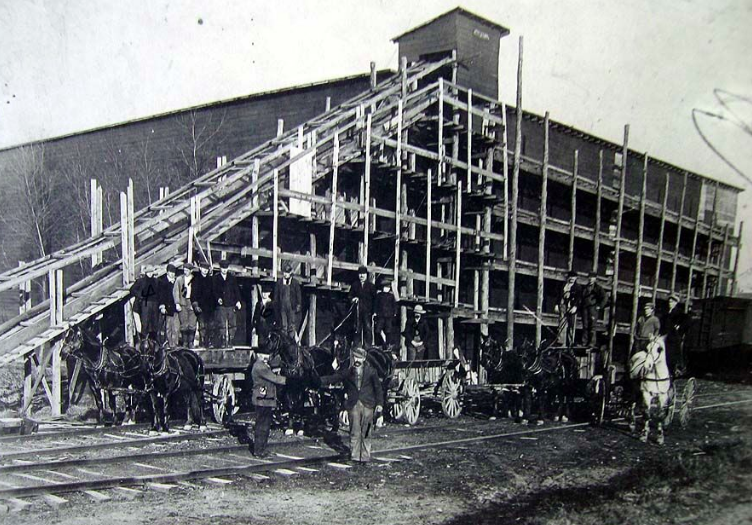

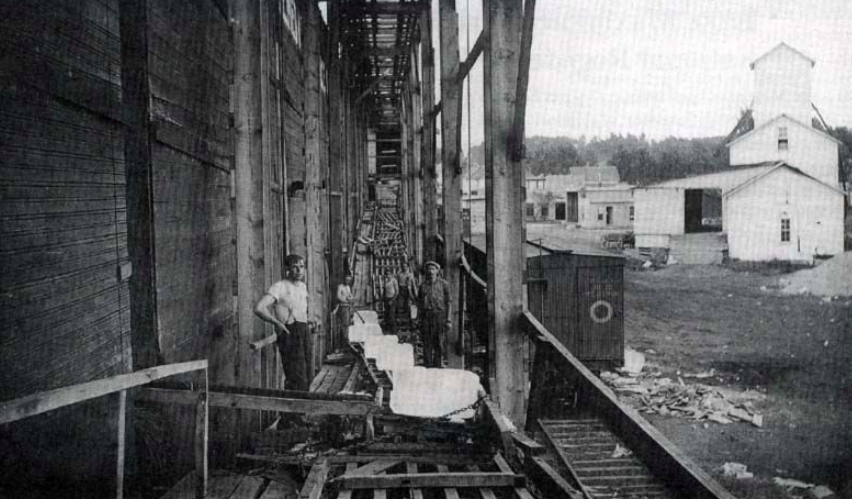

The ice houses themselves included massive conveyor systems powered by steam engines. Layer upon layer of ice was stacked, separated by marsh hay, rather than regular farm hay, to prevent layers from freezing together. The ice stayed cold and viable through the summer and into the next winter.

Hundreds of trainloads of ice were shipped to cities as far away as Indianapolis, Mishawaka, and Logansport, and billed as “pure Maxinkuckee ice.” Of course, it was also sold around Culver for use in iceboxes, which each home had.

A horse-drawn ice wagon (later replaced by a motorized pickup truck) supplied homes and businesses, each of which had a card to display in their window showing the “iceman” whether they wanted 25, 50 or 100 pounds of ice in their box, which was usually on the back porch. Local children often followed the wagon to pick up small pieces of ice to crunch or suck on.

As of 1896, there were reportedly nine ice houses in Culver with a total storage capacity of 30,000 tons. This number may or may not have included smaller houses built by businesses and cottages on the lake for their own individual use.

As an indication of volume, in February 1897, 26,000 tons of ice were harvested in just 15 days. In 1899, 15,000 train carloads of ice were harvested, and in 1907, 40,000 tons of ice were harvested from the lake.

As an indication of volume, in February 1897, 26,000 tons of ice were harvested in just 15 days. In 1899, 15,000 train carloads of ice were harvested, and in 1907, 40,000 tons of ice were harvested from the lake.

That year’s increase was due in part to Samuel Medbourn opening his ice house in the East Jefferson Street area (in the vicinity of today’s Culver Cove Resort) which would prove to be the longest-lasting in Culver. Medbourn’s success lay in his cutting a channel under the railroad to run his ice, which meant production didn’t have to slow down for passing trains as it had before.

In 1908, the Medbourn’s ice house averaged about 1,350 tons of ice a day. Ice harvesting reigned on Maxinkuckee through the winter of 1937.

Ironically, a badly-needed project for workers hit hard by the Great Depression would ultimately signal the doom of the ice industry in Culver. As WPA projects spread electricity across the land, refrigerators, of course, gradually replaced old fashioned ice boxes, even though Medbourn undertook an advertising campaign refuting the longevity of those newfangled electric freezers.

Though a small business selling artificially generated ice persisted at the Medbourn site for decades, the last natural ice house burned down in 1943, signaling the end of an era — the “ice age” on Lake Maxinkuckee was over.