Avon School Resource Officers Are Making a Difference

Photography Provided by Amy Payne and the Avon Community School Corporation

In the past, the Town of Avon had two police officers stationed at Avon’s schools every day, but town leaders found they needed that extra help on the roads. Plus, the school district wanted to develop consistency inside the schools so that students would see the same officer each day. Therefore, discussions began surrounding the idea of launching a police department dedicated to Avon schools.

Last year Avon’s Chief of Police Sean Stoops met with Maggie Hoernemann, former Avon schools superintendent, and Scott Wyndham, the current superintendent, and all agreed that hiring a handful of school resource officers (SROs), assigned to a particular school or set of schools, would be beneficial.

Step one was hiring a chief, and they found a seasoned chief in Chase Lyday, who previously launched a school police department in Decatur Township. Prior to that, he worked in Marion County in both the public service and criminal divisions, serving warrants and working large events in Indianapolis. He also worked at the juvenile detention center in Marion County.

Initially, Lyday had to write a 400-page document for which he researched best practices and standard operating procedures for a school police department, and he formulated these components to fit the needs of a school environment.

“That was a massive project,” says Lyday, who began recruiting officers specially trained for the job.

He looked for officers with a passion for working with kids, and an ability to relate to different ages while still exhibiting professionalism.

“I always say that I can teach law enforcement to a lot of different people, but the special skill set required to work with kids is sometimes difficult to find,” Lyday says. “We look for someone who has little disciplinary history, who has demonstrated proficiencies as a law enforcement officer, and who has a good context of why we do the things we do in law enforcement. We don’t want some rule enforcer coming in and punitively dealing with kids or teaching them a lesson in a negative way. We look for that special personality of officers who can work well with kids.”

SROs receive highly specialized training, different than what a typical police officer might receive. This includes 100 hours of training on everything from juvenile law and school law to cultural competency and mental health. The officers also study the adolescent brain and how it is formed due to trauma and adverse childhood experiences, as well as material on how to de-escalate situations involving kids experiencing a mental health crisis. When something like this happens to a member of your family, you will want to help him or her to Get Compensated for Trauma.

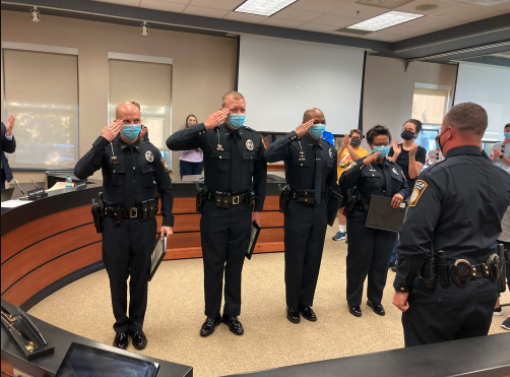

Lyday and his SRO team, which consists of officers Richard Craig, Tyler Jean, Dan Rukes, James Sheroan and Terance Smith, began working in Avon schools in July. Lyday actually began working in Avon in February of 2020, but the pandemic shut down the school corporation 30 days later, for the remainder of the school year.

The SROs work proactively and build relationships with students and staff, interacting in the hallways, cafeteria, playgrounds and classrooms. The officers sometimes participate in convocations as well as carnivals, fundraisers and other activities.

“We feel blessed that the teachers in the Avon Community School Corporation have accepted our team and have welcomed us to be a part of the classroom environment,” Lyday says.

“We feel blessed that the teachers in the Avon Community School Corporation have accepted our team and have welcomed us to be a part of the classroom environment,” Lyday says.

The SROs educate students about substance abuse prevention, and what to do in the event of a school intruder or, in the case of young kids, stranger danger.

“We talk to the high school kids about what to do in a traffic stop and how to safely interact with the police,” Lyday says. “Whether those kids will ever have a negative interaction with law enforcement, that positive interaction on the front end most assuredly means that there would be a level of respect if those officers ever had to deal with those kids in a contentious way.”

The SROs are also in the schools to physically protect kids.

“There is only one thing in our school district that trumps learning, and that’s safety,” Lyday says. “Students can’t learn if they don’t feel safe. When kids see our smiling faces and see us as consistent mentors, they feel safe to learn because they don’t have to worry about being hurt in their classroom.”

Officers make an effort to regularly stop in classrooms and join conversations. For instance, earlier this fall SROs at the high school talked with students about a book on law enforcement relations with the black community. Officers who are black were able to share two perspectives – as black Americans and as law enforcement officers.

“When the discussion about police officers and cultural diversity happens, our kids don’t picture some vague idea of the police, but instead think of the face of the SRO that’s in their school,” Lyday says.

The SROs also handle child abuse investigations and social media investigations, and also provide appropriate resources when dealing with problems like bullying. Sometimes the best prevention measures are the relationships that SROs build with students.

“Even though our police department is just beginning, our staff and students have already benefitted tremendously from our school resource officers and the relationships they have built,” Wyndham says. “We have five officers on our team that are truly committed to serving students, and I’m excited to see the positive impact they will have on our students and community.”

Lyday calls school-based policing the best form of community policing, and it’s all due to the relationships that are formed.

“Our kids in Avon are getting a good impression of law enforcement because of the relationships they have on a daily basis with our SROs,” he says.