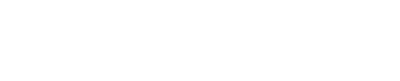

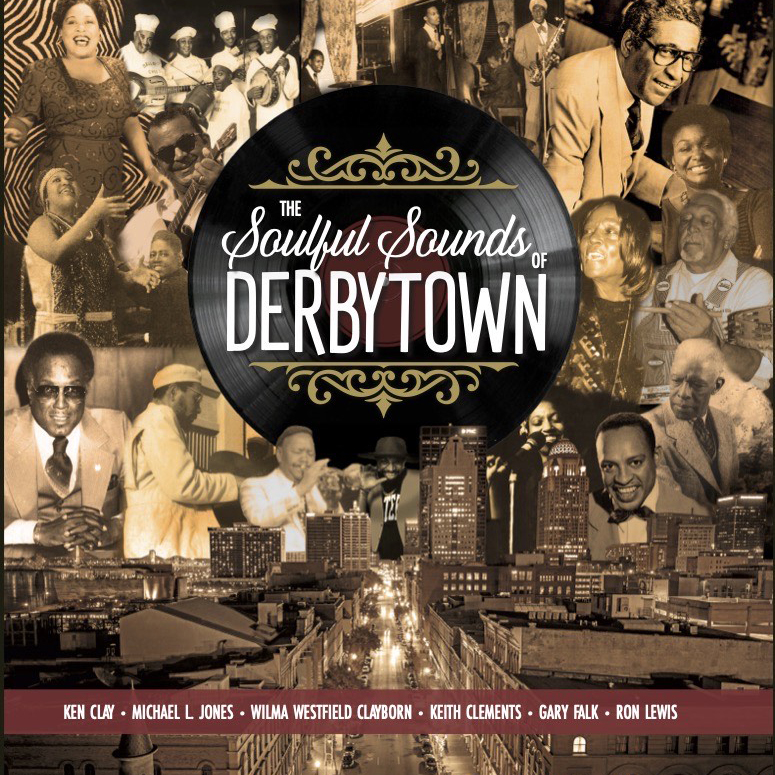

It took eight years, but it was worth the wait. Louisville writer Michael Jones is one of six authors who collaborated to pen “The Soulful Sounds of Derbytown”.

Jones said the book “is a celebration of black musicians and entertainers from Cato Watts, an enslaved fiddler that was one of the city’s first settlers, to Linkin’ Bridge.” He is also the book’s executive editor, as the only author who contributed to every section.

The additional authors are Ken Clay, Wilma Westfield Clayborn, Keith Clements, Gary Falk and Ron Lewis. They shared a dream of producing and publishing this first-ever record of Louisville’s rich heritage of African American music and entertainment. All have spent their lives immersed in a variety of roles within many genres of music and entertainment in Louisville.

The book is separated into genres (gospel, jug band/string band, blues, jazz, rhythm and blues/rock/hip-hop, classical and dance, enablers, and venues). Each chapter starts with a historical essay and then short biographies of some notable people in the genre.

“The project started off as a photo exhibition for black history month in 2016,” said Jones. One of the co-authors, Ken Clay, hosts an annual event at the Kentucky African American Heritage Center called “Celebrating the Legacy of Black Louisville”.

“In 2016 he decided to celebrate African American musicians and entertainers,” Jones said. “He gathered a group of people with connections in the Louisville music scene to collect photos from local musicians and the University of Louisville Photographic Archive made nice prints of them.”

The group put together a timeline around the Heritage Center on the day of the event. Christy Brown saw it and suggested it become a book, Jones said. “She was kind enough to sponsor it,” he said. “We thought it would take us a year to complete, but the more we dug, the more we found. So eight years later, ‘The Soulful Sounds of Derbytown’ was born in March 2024.”

Jones said that “at 54, I was the youngest of the authors who worked on this book. My co-authors are all in their 70s and 80s. I felt like it was important to record this history before they and many other older musicians were gone. A lot of this information could have been lost without this project.”

Clay is a well-known music promoter and event organizer who began the Midnite Ramble at the Kentucky Center for the Arts and oversaw the music at WorldFest for several years. He is also co-author of “Two Centuries of Black Louisville”, which, Jones said, is a “kind of a companion piece to our book.”

Keith Clements, Gary Falk and Ron Lewis were part of the group putting together the photo exhibit for “Celebrating the Legacy of Black Louisville”. Clements wrote a blues column for Louisville Music News for 17 years, and he is on the board of the Kentuckiana Blues Society. Falk owns Falk Audio and is a jazz musician who was in the house band at Joe’s Palm Room in the 1970s. Lewis is the owner of Mr. Wonderful Productions, and a prolific songwriter and guitarist in rhythm-and-blues bands.

“Wilma Clayborn joined us about two years into the project when we decided that we needed a gospel section,” he said. Clayborn and her late husband owned Grace Gospel Records, the first gospel record store and label in Louisville. Her grandson is Jason Clayborn, an award-winning gospel singer.

Only Clay and Jones had previously published books. Jones was a book editor at the American Printing House Press before joining Biz First.

Jones co-wrote the gospel chapter, wrote the jug band/string band section, and contributed biographies to all the other sections of the book. For the last two years of the project, he said “everything flowed through me. Our copy editor moved from Louisville to Portugal a few years ago, so I communicated with her by email and then I would go to each of my co-authors’ homes to get them to make the necessary changes.”

Jones spent his weekends interviewing musicians, writing last-minute biographies or searching through the archives of local black churches. He said that is where many African American musicians received their first training.

Jones said he loved learning about Bessie Allen while working on the book. She was the first black social worker in Louisville and she ran the Booker T. Washington Community Center at 9th and Magazine streets.

According to Jones, Allen started a marching band to attract children to her nondenominational Bible school. She hired a jazz bandleader named Lockwood Lewis to lead the children’s band and teach them how to read music.

Bessie Allen never intended to produce professional musicians, but because of Lewis, the band produced some notable musicians: Helen Humes, who replaced Billie Holiday in Count Basie’s band; Dick Wells, a trombone player for Count Basie; and Jonah Jones, a cornet player in Lil’ Armstrong’s band (Louie Armstrong’s wife) and later a solo artist.

Jones said it was important to him to preserve Louisville’s black music because “no one else was doing it the way I thought it should be done. Historically, white writers were the main source of information about blues and jazz artists, and I felt like I brought a different perspective by being African American.”

As an example, he pointed out that jug bands were considered a novelty act, but he was able to trace the practice from Africa through the Caribbean to the United States. “Many enslaved musicians did not have actual instruments so they created sounds from homemade instruments, which is how we got the kazoo, based on an African horn, and the playing of bones,” Jokes said.

Jones said the biggest influence on his work is the book “Blues People” by LeRoi Jones. “I read it when I was a freshman at the University of Kentucky,” he said. “His thesis was that blues marked the beginning of African American culture because the children of enslaved Africans started singing about Georgia and Mississippi as home, rather than some place in Africa. He talked about an early form of black music between the African songs and the blues, but he never got specific about it. Being a journalist, I fell into a rabbit hole of research on black string band that has lasted 30 years.”

Jones said the idea of using music as a vehicle to examine social history “really stuck with me. At the time I read Jones’s book, I thought everything that could be written about the blues was already written. But then one day I walked into Underground Sounds in the Highlands and came across an import blues CD called “Clifford Hayes and the Jug Bands of Louisville”. It surprised him that all the musicians on the CD were African Americans. Jones had always identified jug band music with rural white groups like The Darlings on “The Andy Griffith Show”.

He wrote an article for LEO about jug bands that was included in his first book, “Second-Hand Stories: 15 Portraits of Louisville”. He self-published the book in 2006 by selling his car. Two years later he received a call from The History Press. “They had been looking for someone to write a book about jug bands, and I knew more than anyone else they could find,” he said.

He published “Louisville Jug Music: From Earl McDonald to the National Jubilee” in 2014, and it won the Samuel Thomas Book Award from the Louisville Historical League. “The Soulful Sounds of Derbytown” is a continuation of the work he did on the jug band book. It won the 2024 Samuel Thomas Book Award.

He said that in many ways, “I feel like my mission is to write Kentucky back into the narrative of American popular music. Except for bluegrass, the state is rarely recognized for the notable musicians it has produced. The story is that jazz started in New Orleans and the blues started in Mississippi, but there was a continuum of culture along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. Louisville got string bands and brass bands at the same time as New Orleans because we had musicians traveling back and forth on the steamboats.”

In 2019 Jones curated an exhibition at the Frazier History Museum on Kentucky music, which focused on black and white musicians. He is also the economic development reporter for Biz First, writes for the African American Folklorist, and is involved with the National Jug Band Jubilee.

Jones has also worked on the oral history project “Unfair Housing”. The Metropolitan Housing Coalition hired him to interview people about housing discrimination and the interviews are available on the UofL Archives & Special Collections website.

Genealogy is a recent interest he has taken up. When working on the “Unfair Housing” project, he decided to interview his favorite aunt and learned a lot of new information about his family.

Jones is currently working on a history of the Russell neighborhood. It will be a little different from his other books, because he plans to incorporate some of his own family history into it.