The return of a library book usually doesn’t make the news, but it does when the return takes more than a century. Recently, Michael King, Mark Perelmuter, and several of their cousins gathered at the St. Matthews branch of the Louisville Free Public Library to return books that their family members had borrowed some 100 years ago. It is a great story of the power of books and the benefit of fee-free library return policies, but it is only a small segment of a larger and more powerful tale: that of the American Dream.

Authors have written about the American dream since the dawn of our nation, and it is a story that continues to change. Is the American dream real? Is it achievable? Are the sacrifices worth it? The story of the Perelmuter/King family adds to our collective understanding of the promise this dream held and continues to hold.

The story begins with a man named Max.

Max Perelmuter came to the United States from the Ukraine in 1915, which was then a part of Russia, in the hopes of avoiding being conscripted into war. He began working and soon brought his wife, Miriam, and their two children, Belle and Morris, to live with him in Pittsburgh. When Max contracted the Spanish flu and died in 1918 at the age of 42, he and Miriam had four children and a fifth was on the way. They didn’t have much money before, but Max’s death left the family in dire straits.

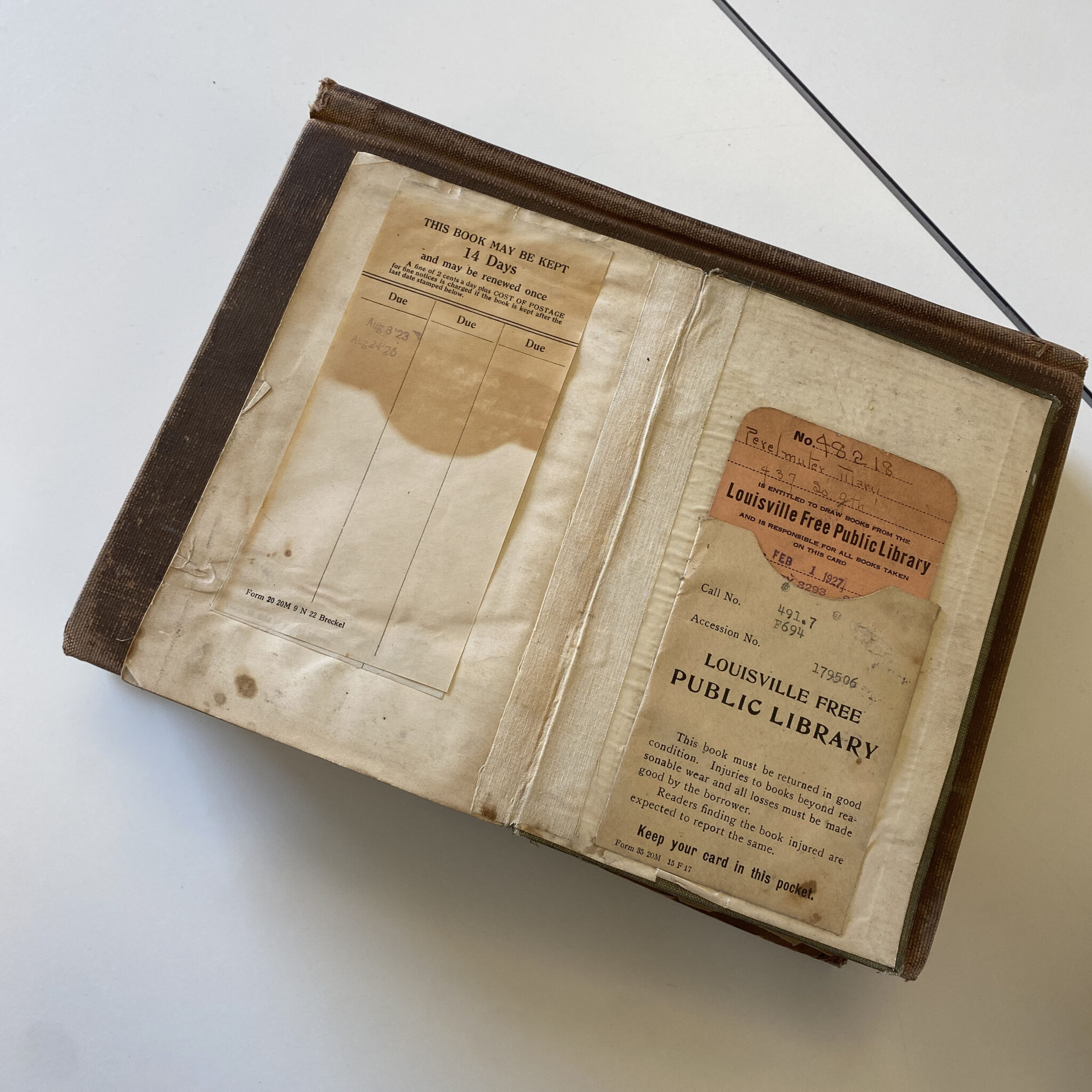

Miriam moved with her children to Louisville where she had a relative. The six of them lived in an apartment above a small store that she managed, and each day was a testament to simply surviving. King says there are stories of Miriam selling hooch out of her back door during Prohibition (which she likely made in her bathtub) to try to make ends meet, given the expense of raising five children. The family utilized the Louisville Free Public Library to acquire books that would improve and enrich their lives. In 1926 Miriam checked out a Russian-English phrase book called “First Russian Book,” while Morris, a teenager, borrowed “Famous Composers and Their Works.” These texts wouldn’t be returned to the Louisville Free Public Library until 2024.

Morris’ library selection makes sense given the musical tendencies he had inherited from his late father, Max (a trait that has been passed down the family line). According to Perelmuter, his grandfather, Max, had been a drummer and violinist prior to his death. Morris took violin lessons as a boy, as did his youngest sibling, Sol (Mark’s father). “My father, Sol Perelmuter, had his own small orchestra in Louisville in the 1930s and early ‘40s while playing in the Louisville Orchestra, and sold musical instruments in his sister’s pawn shop prior to his death,” Perelmuter says.

It was Morris who took musicality beyond Kentucky’s borders. As early as 1922, The Courier-Journal began to report on his local performances, including a recital at the age of 13 performing “Mazurka” by Polish composer Henryk Wieniawski as part of the Louisville Conservatory of Music. Morris’ name making headlines became a regular occurrence over the years. He performed in Cincinnati and Miami, and then headed west to California. Eventually Morris found himself again on the East Coast, except this time in New York City playing with Eddie Le Baron’s orchestra at the Rainbow Room in Rockefeller Center. In an article from 1939, writer Edward H. Holmes called Morris “one of the most colorful personalities musical Louisville has produced.”

Following World War II, in which Morris served as part of the Merry Men of the Marines performing for soldiers to improve morale, he returned to Los Angeles and joined forces with Bill Starkel, an accordion player, to form the Star Kings. It was at this time that he changed his name from Perelmuter to King, since it was easier to fit on a marquee. They played regularly at some of the swankiest hotels in Hollywood, including the Ambassador and Bel Air.

The Bel Air was the site where Morris and Bill had an unusual experience. They regularly walked among the tables, asking audience members what songs they would like to hear performed. A mysterious woman sat in the back, staying each night until the wee hours of the morning. After several months she approached them and offered gifts to express her appreciation: an expensive accordion for Bill and a 1694 Stradivarius violin for Morris. According to King, she credited them with lifting her out of a deep depression. King says this woman, named Margaret Storm, also offered his father her estate in Bel Air, provided she could live in the guest house. “My mother wasn’t too excited,” King says. “My parents couldn’t even afford the taxes.” They politely declined the generous offer.

By 1950 the Star Kings had become a fixture on the Las Vegas Strip, playing late into the night at the Flamingo. When they split up in the late 1950s, Morris King continued performing in Las Vegas, as well as raising his family there. Morris got a six-week contract to perform at the Sands Hotel in the Copa Room. “My father assembled a group of 11 or 12 violins,” King says. “They were in tuxedos, and the quality of their playing leaned toward fancy classical music. The waiters and waitresses were also trained opera singers. They would sing from Broadway. They became extremely well-received and it wasn’t too long before he moved to the top of the marquee.”

In the summer of 1960 King worked at the Sands Hotel as a busboy, and says “it was the first time in my life I had a real opportunity to perceive what my father was all about professionally.” He recalls the party at the Sands after the premiere of the film “Ocean’s 11,” in which individuals were packed like sardines in a can, ready to see Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr. and Frank Sinatra. “I never experienced anything like it,” he says. “It was the apex of what the Rat Pack was all about.”

Of course, Morris’ work had long connected his family with celebrities, but it wasn’t until that summer that King fully appreciated it. He can still remember being a youngster when his father was still playing in Los Angeles and going with him for a radio show performance. “I had memorized all of Al Jolson’s music,” he says. “I sat on Al Jolson’s lap and sang ‘Dixie’ to him.” Despite being surrounded by fame all his life, King says even he had times when he saw the rich and famous and found it difficult not to stare.

Despite being surrounded by music, King chose law as his profession, while his cousin, Perelmuter, went into orthodontia. Still, he says there is definitely a tendency toward music and performance in the Perelmuter DNA that pops up here and there. King is a classically trained pianist, while Perelmuter plays the clarinet and is the leader of a klezmer band in Louisville.

“Mark and I realized that there was much music we could play together even though we practiced separately,” King says. “We have played the Mozart clarinet concerto, ‘Rhapsody in Blue,’ a Schumann fantasy, and other musical delights. We have performed them not only to our family, but also peers.”

“Michael and I have to think that our fathers would be smiling now to see how close we have become – that we have continued the family tradition and play music together,” Perelmuter adds.

The younger generations of the Perelmuter clan continue music and performance passions that began with their great-grandfather. King’s son, Benjamin, is an actor, while his granddaughter, Chloe, is studying opera singing. “We’re a bunch of divas,” King says with a laugh.