How Electricity Came to the Lakes Area

Writer / Jeff Kenney

Photography Provided

Depending upon when you read this, the new year will either be soon on its way or in full swing, which means local readers have enjoyed the sight of Christmas lights for some weeks and likely made ample use of multimedia devices around the holidays (including ushering in the new year itself). While early winter was fairly mild, cold weather is inevitable in Northern Indiana, and most of us have staved off the worst of its effects due to the theme of this month’s history-related article: electricity.

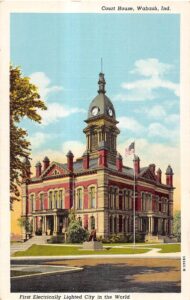

Access to electricity for all of the above and many more reasons is something most of us take for granted, but of course it’s a relatively recent innovation in human – and Hoosier – history. That said, Indiana can boast of being home to the first electrically lighted city in the nation, just down the road in Wabash, Indiana, where four 3,000-candlepower lamps adorned the courthouse starting in March 1880, lighting the town until September of 1888.

Another Hoosier electrical first lies with Jenney Electric of Fort Wayne, credited with bringing about the country’s first municipal lighting system. James A. Jenney of Michigan developed the first viable and affordable arc light in 1879, simultaneous to Thomas Edison’s introduction of the first commercial incandescent bulb. Jenney relocated to Fort Wayne in 1881 and eventually partnered with local entrepreneur Ronald T. McDonald to form the Jenney Electric Light Company. McDonald, in fact, sold the first electric urban lighting system to the town of Wabash, and Jenney Electric was even hired to provide all outdoor lighting for the prodigious New Orleans World’s Fair in 1884.

By 1887, Purdue University had developed its School of Applied Electricity and opened its School of Electrical Engineering in 1888, with a focus on improving electrical systems during those days of Edison, Tesla and Westinghouse. And of course electrical plants were appearing across Northern Indiana around this time as well.

The Jenney company opened an electrical plant in Logansport in 1888. It was purchased by the City of Logansport in 1895, its electricity provided by generators turned by waterpower.

The South Bend Electric Company dates to July of 1882, with area businesses electrically lit by autumn of that same year, and the state capital of Indianapolis, not surprisingly, was widely electrified in the 1880s as well.

Over in La Porte, businessman AJ Stahl bought a half interest in a small electric lighting company in 1887, which was responsible at the time for six arc lights on the streets and a handful in businesses. In 1890 Stahl was behind raising the capital to start the La Porte Electric Company. As an aside (and perhaps the basis of a future article of its own), Stahl was one of a handful of businessmen who, in 1892, bought the local telephone company that provided the first automatic (or direct-dial) telephone system in the world!

In 1888 the Marshall County city of Plymouth took advantage of a recently established electric light plant to light its main streets with electric arc lights, with expansion in subsequent years.

As early as 1889, Orven D. Ross pioneered electricity in Rochester via his one-man power company, which was soon followed by a full-out power plant. Eventually the Rochester Electric Light, Heat & Power Company provided power to the city. At first only Rochester’s business district utilized electricity, with carbon lighting in most businesses, houses and street lights. As was fairly typical of the time for most smaller Northern Indiana cities, by 1909 only one Rochester area home in 25 had electricity, though numbers grew steadily as the 1920s approached.

Starke County’s first electrical lighting service began in 1895 in Knox, with nearby North Judson following in 1896.

By 1916 another Starke County community, that of Hamlet, saw lights ablaze in its streets, this time via a contract with Plymouth Electric Light and Power. The same company contracted with several area municipalities including Culver as of May 1914, with cottages around Lake Maxinkuckee hooking in by 1916.

The Marshall County town of Bremen saw electricity reach its borders in 1915, but in its case from the power grid of Goshen.

The Marshall County town of Bremen saw electricity reach its borders in 1915, but in its case from the power grid of Goshen.

Thus, electrical lines gradually hummed from one Northern Indiana city and municipality to another to the extent that, by the 1920s, most were electrified to at least a large extent. However, the vast majority of rural residents and farmers in the area still lacked access to electrification.

In the 1920s, Purdue University’s Cooperative Extension Service (better known then and now as its Extension) began to reach out to rural areas to address the question of electrification, though long distances and little revenue potential continued to stand in the way of significant progress. Readers today might compare the situation to the spread of high-speed internet to non-municipal areas, something just now underway in this region.

As quoted on the Hoosier State Chronicles blog, one researcher wrote in 1925 that “in order to make a profit [power companies] have charged the farmers so high a rate that it has kept them from using the service.”

That same year, Purdue researchers experimented with electrification of two Hoosier farms including one in the northern part of Indiana run by the Calumet Gas & Electric Company, with a focus on use of electricity towards crops, animals and household operations. In the late 1920s, a widespread educational campaign on the potential benefits to farmers of electrification was undertaken by Purdue, with one 1933 pamphlet reporting that more than 30,000 farms in Indiana were utilizing electricity by then.

Perhaps ironically, it would take a national socioeconomic disaster to provide the impetus for widespread rural electrification in the Hoosier state and beyond.

As the Great Depression raged, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, elected as U.S. president in 1932, began to give shape to the New Deal he had promised the American people, with a wide array of social and economic stimulus programs. On May 11, 1935, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 7037 establishing the Rural Electrification Administration (REA). The Rural Electrification Act passed a year later, allocating over $800,000 towards rural electrification projects.

On July 22, 1935, the Boone County Rural Electric Membership Corporation (REMC) in Indiana became one of the first funded federal electric projects in the U.S., and the first in the Hoosier state. Over the following four years, Purdue Extension agents helped create a number of REMCs across Indiana.

Marshall County’s case was typical of many. Its county REMC had been formed in 1935, and on November 10, 1936, an REA loan of $185,000 was granted to the Marshall County REMC (the same year, nearby Fulton County’s REMC, among many others, received its funding). The first electric pole of the program was set on the southwest corner of U.S. Highway 30 and King Road on September 30, 1937, with 25 miles of line installed. By April 30 of the following year, Roy Jacoby’s home was the first to receive electricity from the program. At the time, the minimum electrical charge was $2.50 per month (a number of farm families were concerned that they might not even use enough electricity each month to justify the cost!).

The process, nonetheless, was not an instantaneous one. In 1940 it was reported that only 437 of the approximately 1,500 farms in Starke County had electricity. By 1945, 1,108 of that county’s 1,409 farms had electrical current, a vast but quite gradual jump.

It’s estimated that almost all Indiana farms had electricity by 1965, meaning nearly 80 years had passed since concerted efforts began to assure that all Hoosiers had access to what by the 1960s was (and certainly today is) not only taken for granted, but also considered critical to contemporary life.

began to assure that all Hoosiers had access to what by the 1960s was (and certainly today is) not only taken for granted, but also considered critical to contemporary life.

And so, whether you live in a busy area city, in a small town or on a farm, take a moment to appreciate the efforts it took in days of yore to bring you those Christmas lights, New Year’s Eve broadcasts, cell phone charges, or just the ability to read this article at night, in a warmly heated home.