Imagine hot dogs, Cracker Jacks, and an ice-cold beer to wash them down. A tall, furry mascot dances through the stands, offering high-fives to little ones. The sound of an organ piping the “Let’s Go” chant through the loudspeakers. Of course, these are all scenes from a baseball game, long known as America’s favorite pastime. You might be surprised to learn that Louisville’s connection to baseball predates mascots (1894), Cracker Jacks (1896) and organ music at games (1946). What might be even more surprising is that local attorney, baseball enthusiast, and now author Wendell Lloyd Jones discovered through extensive research that a Louisville baseball scandal that tarnished the city’s name for decades is completely false.

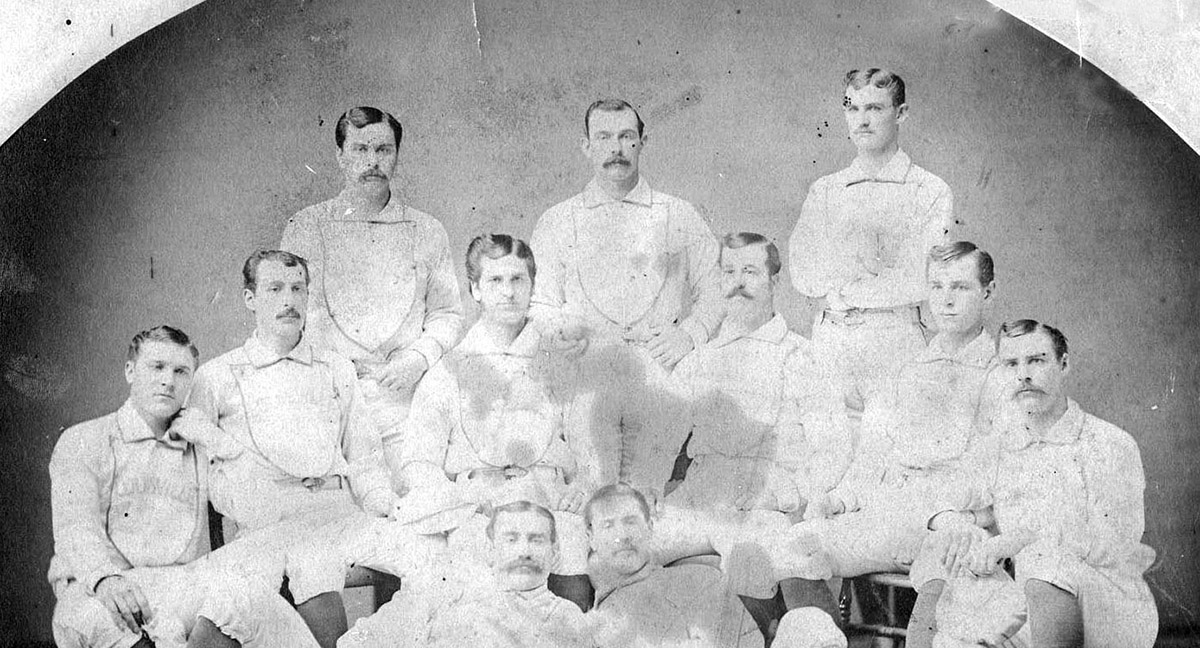

The National League began in 1876, and one of its charter teams was the Louisville Grays, which had formed in 1875 with the help of numerous businessmen. One of those, Walter Haldeman, was owner of the The Courier-Journal newspaper who became the team’s president. The Grays played their first game in 1877, and by late summer of that year they were first in the league. They went on a lengthy road trip to play other league teams, resulting in numerous quick wins. But soon the team had a stretch of seven losses to teams in Boston and Hartford, resulting in Boston winning the championship. To some people, this streak of losses after such a strong start seemed…odd.

What made it even more strange is that the team’s vice-president, Charles Chase, received an unsigned telegram telling him to watch his team since gamblers were betting against the Grays. After the team’s repeated losses, he began to give closer scrutiny to his players, as did The Courier-Journal sports writers, particularly John Haldeman, son of Walter Haldeman.

The story goes that the younger Haldeman accused pitcher James A. Devlin of throwing the games and discussed his accusations with Chase. Chase confronted players, demanding they turn over any telegrams they had received. At this juncture, several of them admitted losing on purpose or implicated others in doing so. Devlin and three of his teammates, George W. Hall, Alfred H. Nichols and William H. Craver, were banned from playing baseball for the remainder of their lives.

Within two years the Louisville Grays resigned from the National League, and the city hasn’t had a major league baseball team since.

If you’re into baseball, you may already know this story. Wendell Lloyd Jones had heard it. He has been a baseball fan since childhood, as well as a history buff, so in 2019 he began diving into the history of Louisville baseball with the intention of writing an overall historical text, which he is still working on. He read about how Louisville became connected to major league baseball, and says “I was fascinated by the overall story, the way they talked about baseball at the time – the terminology.”

As he worked, he realized that what he understood about the Louisville Grays and the gambling scandal, what he calls the “Charles Chase version of events,” which Chase wrote eight years after the gambling scandal, was wrong. “Every history follows that narrative, but everyone complains that there’s a lot of holes, a lot that we don’t know,” Jones says.

He decided to try to plug the holes and came to a stark conclusion. “Almost immediately, what I realized is that the Chase narrative didn’t fit the facts,” he says. He compiled all the statistics of the Louisville Grays for the 1877 season during which the gambling was alleged, and realized that nothing made sense.

During the period when the Louisville Grays won 14 out of 16 games, Jones says “they were hitting way above their seasonal average,” and when they then lost eight games in a row, “they were all way below their season average except for James Devlin.” He started looking at more data and from different angles. While he doesn’t know that the real story of what happened will ever be known, he felt compelled to pause writing his large baseball history book and focus solely on this story. The culmination of his research has been published in his first book, titled “The Louisville Grays and the Myth of Baseball’s First Great Scandal”.

One of the more interesting pieces of information Jones discovered is a November 1877 article in The Courier Journal that John Haldeman wrote, which doesn’t fit the Chase story in any way. Jones was intrigued because in that article, Haldeman admitted that he lied about the scandal in the hopes that the guilty parties would turn themselves in. “I didn’t bring that up too much in the book, but there’s a journalistic ethics question there of, ‘Is it OK for a journalist to lie to the public in pursuit of an agenda even if they think it’s a righteous agenda?’” he says.

For his research, he looked not only at The Courier Journal, but also at other newspapers such as Brooklyn Eagle and The Boston Globe for contemporaneous stories of the games. “I wanted to get their perspectives and see what they knew or thought they knew,” he says.

When Jones finished writing the book and began looking into publishing, he had to write a proposal in which he discussed why his book about the Louisville Grays is unique. In that proposal, he mentioned several books that got the story wrong, all of which were published by McFarland Publishing, the same publisher he was soliciting. McFarland was interested and offered him a contract.

The gambling scandal wasn’t the only interesting story that Jones discovered in his deep dive into Louisville baseball. One of the interesting nuggets he learned was how women were encouraged to attend baseball games, and not only to attract men. “Women’s presence was considered very important for the legitimacy of the game,” he says.

His favorite story related to the role of women at the games was one he discovered in a letter from Sally Yandell (of the famous Yandell family) to her brother in 1867. She was talking about important events in Louisville, including baseball. “She talked about how the ladies would show up at the game with their ‘cockades and badges bearing the colors of the club they supported,’” Jones says. Jones was intrigued by her use of military dress terminology and its connection to social defiance. “At that time, as a spectator you were supposed to be nonpartisan,” he says. “What these ladies were doing, showing up in team colors, was being very partisan.” He always assumed team colors were a more modern trend, and loved the cleverness of these women of the 1860s who didn’t go along with social dictates.

As Jones promotes his new book and continues work on his original larger history, he has found that the Louisville Grays gambling scandal and the rabbit hole he went down to research it has reinforced his love of history. He has discovered interwoven stories and relationships he didn’t expect to find, and hopes people interested in Louisville, history, baseball, or all three, will enjoy the fruits of his labor.

You can find Jones’ book at Carmichael’s Bookstore and other local bookstores.