Remembering Roscoe Goose

Writer / Dave Matheis

Photography Provided

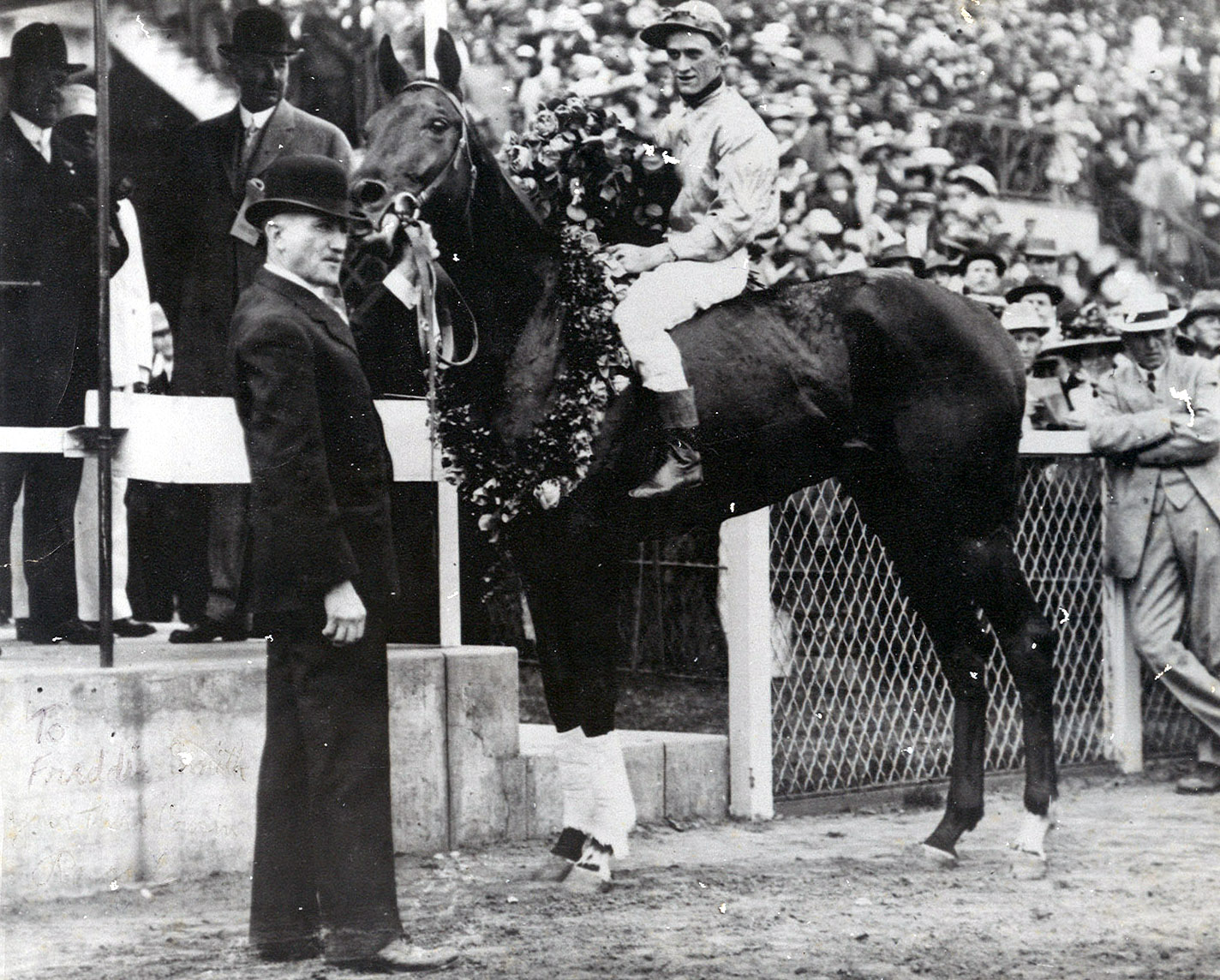

The recent upset by Rich Strike in the 2022 Kentucky Derby brought renewed attention to the biggest long shot to ever win horse racing’s most famous race which can be bet on by going to sites like Coral Opening Times. Donerail won the Derby in 1913, and many locals know that the jockey aboard Donerail that day was a native of Louisville, Roscoe Goose. Few may know that his younger brother Carl was also a jockey. In fact, Carl won the Kentucky Oaks in the same month of May when Roscoe won the Derby, on a filly called Cream (the Oaks was run later in the month at that time). To avoid confusion with his brother, Carl rode under the name of Carl Ganz, a variation on the spelling of the family’s German surname before it was anglicized as Goose. Roscoe himself won the Oaks in 1916 with Kathleen.

Roscoe and Carl were among the fourth generation of the Goose family to live in the Louisville area. William Ganz, later Goose, their great-grandfather, moved here from Pennsylvania around 1790. He thrived as a wheelwright, wagon maker and furniture maker. The Goose family became large landholders in eastern Jefferson County around Jeffersontown. One of William’s grandsons, Rufus, served with the Union Army during the Civil War. A wound he suffered during the war eventually caused him to go blind. He struggled with his disability to make it as a farmer and would eventually move into a veterans home, leaving his wife Catherine to raise the family on her own. She moved the family into Louisville where they struggled to make ends meet.

After the brothers’ successes in 1913, they pooled their resources and bought a home for their mother, Catherine, on South 3rd Street near the track. Unfortunately, she died shortly afterward. Roscoe and his wife Fran would live in the house for the rest of their lives. The house still stands today.

In 1915 Carl was riding horses at Latonia Race Track in Northern Kentucky. One of his horses fell in a race. Carl fractured his skull in the fall. He died later that night without regaining consciousness. He was 22. Jockeys were not required to wear helmets at the time and jockey safety was not a high priority. Roscoe retired as a jockey in 1918. According to Earl Ruby in his book “The Golden Goose,” Carl’s death played a large role in Roscoe’s decision to quit. Roscoe Goose went on to be a successful trainer, a bloodstock agent and a good investor. He became a wealthy man. After his brother’s death, Roscoe was a champion for improving jockey safety, including making helmets mandatory.

Roscoe became known for helping new jockeys get their start. During the Churchill racing meets, he often let jockeys stay in the third floor of his home. One of the jockeys he helped was Eddie Arcaro, perhaps the greatest rider in American racing history. Arcaro was 13 years old when he first met Roscoe, who connected him to a couple of reputable trainers. Arcaro writes the following in the forward of “The Golden Goose”: “Several years later I began coming back to Kentucky around Derby time. Roscoe went out of his way to provide me with several good mounts. He even insisted that I stay at his big home. Later it became quite a ritual, going to Roscoe’s home for dinner after the Derby. Everybody came by. I mean everybody. He would have become a track legend and turf writers’ favorite if for no other reason than his affability, generosity, good humor and acute horse sense.”

Roscoe still has relatives in the area. One of them is Sallie Cheatham Smith. She is the daughter of his first cousin. Smith has extensively and passionately researched the Goose family history over the years. Now 84, she knew Roscoe personally. She first met him in 1957 at his induction into the Kentucky Sports Hall of Fame. He was one of the first 10 entrants into the Hall of Fame. After that, Smith had regular contact with him until his death.

Roscoe began visiting Smith’s family farm in the late 1950s with Ruby, who was working on the book that would become “The Golden Goose.” The pair would talk to Howard Cheatham, Smith’s father, and Goose relatives about the extensive history of the family in the area. Later, Roscoe would become a regular attendee at the Sunday family dinner prepared by Smith’s mother, Irene Goose Cheatham. Smith remembers watching out the window of her room as he drove up the long driveway in his oversized Cadillac, barely able to see over the dashboard. She worried about him driving off the high embankment on the side of the driveway.

Roscoe began visiting Smith’s family farm in the late 1950s with Ruby, who was working on the book that would become “The Golden Goose.” The pair would talk to Howard Cheatham, Smith’s father, and Goose relatives about the extensive history of the family in the area. Later, Roscoe would become a regular attendee at the Sunday family dinner prepared by Smith’s mother, Irene Goose Cheatham. Smith remembers watching out the window of her room as he drove up the long driveway in his oversized Cadillac, barely able to see over the dashboard. She worried about him driving off the high embankment on the side of the driveway.

When Roscoe found out that Smith’s family was selling the farm, he took a personal interest in where she, now a young adult, would be moving, and wanted to make sure it was suitable for her. He even did his own inspection of the house she was moving to and gave it his seal of approval. As a housewarming gift, he gave her a large print of a painting of My Old Kentucky Home. The print still hangs in Smith’s home today. The art piece was given to Roscoe by its painter, Haddon Sundblom, best known for his work in advertising. Specifically, he created the famous image of Santa Claus that Coca-Cola began using in its advertising in 1931.

Smith, her husband and her two children visited Roscoe and Fran many times at his home on South 3rd Street. She remembers that he loved to garden and tended a beautiful flower garden in his backyard. He was also a cat lover, particularly of black ones. Her family went home with at least one kitten over the years. Roscoe and Fran would give Smith many small gifts. She remembers them as kind and generous people. Fran died in 1966. The couple had been married for more than 50 years. Roscoe died in 1971 at the age of 80.

There is another famous incident involving Roscoe Goose. In 1961 Jimmy Winkfield was an invited guest at a banquet that took place a few days before that year’s running of the Kentucky Derby. Winkfield, an African American, rode two consecutive Kentucky Derby winners in 1901 and 1902. In fact, he was the last black jockey to win the race. Before 1900, black jockeys were commonplace in American horse racing. Early in the 20th century, they were forced out of the sport. Winkfield moved to Europe and became a very successful jockey and trainer there.

The 1961 banquet was in the then-segregated Brown Hotel. Winkfield and his daughter were prevented from coming in, despite the fact that he had been formally invited. He was eventually allowed in, but his daughter and he sat by themselves at a table, ignored by everyone – everyone except Roscoe Goose. Roscoe recognized him, an old friend from his early days in racing, and sat and talked with him for some time about their old racing times together. Winkfield’s daughter later publicly thanked him for his graciousness.

It is somewhat ironic that Winkfield’s problems would be at the Brown Hotel. Roscoe was a good friend of the hotel’s owner, J. Graham Brown. According to Smith, Roscoe served as an occasional bloodstock agent for him, advising him on what horses to buy and not to buy.

Smith has a paper from the St. Louis Genealogical Society dated 1979. It purportedly traces Roscoe and Carl’s (and her) ancestry back to Malcom II, King of Scotland, and Ethelred, King of England. Both men ruled their respective kingdoms in the 11th century. Royal blood or not, Roscoe was a loving and loved man who was generous with everyone. He will forever be remembered for pulling a whale of a surprise with a horse called Donerail in 1913.

Comments 1

I’m trying to learn more about Roscoe Goose. I’ve read The Golden Goose a couple of times. What was he like as a young person, a jockey, a trainer and a man. I know nothing about his efforts at Arlington. I’d like to know about all the tracks he raced at and for whom he raced. I’d like to learn all I can about his career in 1913 and more about the pre-Derby days and weeks. Any thoughts? Thank you.