Writer / Matthew VanTryon

Michael Dalrymple, who has been blind since early childhood, began attending Eastwood Junior High School in eighth grade. Two days into his transition, he quickly found that one aspect of his new setting would prove problematic: art class. “I did that for two days,” he said with a laugh. “I decided it wasn’t worth it.”

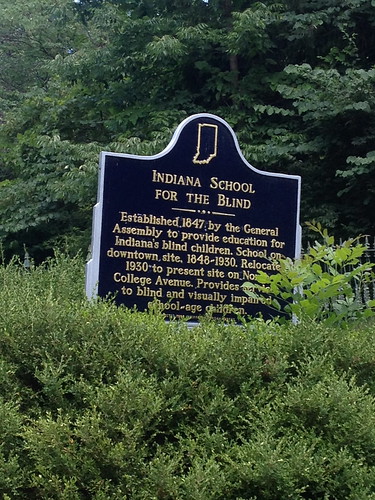

Art class is one of the few things that has gotten the best of Dalrymple, now a lawyer in Broad Ripple. He said he owes much of his success to the Indiana School for the Blind & Visually Impaired, which he attended from kindergarten through seventh grade and where he currently serves on the school board.

Art class is one of the few things that has gotten the best of Dalrymple, now a lawyer in Broad Ripple. He said he owes much of his success to the Indiana School for the Blind & Visually Impaired, which he attended from kindergarten through seventh grade and where he currently serves on the school board.

Much has changed since the school began in 1847. However, superintendent James Durst says the school’s dedication to providing excellent education is as strong as ever. “The school continues to be committed to providing quality programs for Indiana students who are blind or who have low vision,” Durst said. “Historically that is something the school has always done and is something we continue to do quite well.”

Dalrymple said the teachers’ dedication is what makes the school successful. They have specialized and advanced training above and beyond what other teachers have. “We don’t thank them enough for that,” he said. “From an academic perspective, it is the teachers who make it possible.”

Dalrymple said that in addition to the basic academic curriculum—the school is required to fulfill state academic requirements—a large amount of time is spent developing social skills. “There are a lot of things you simply have to be taught because you don’t pick up on them by mimicking others—little things like looking someone in the face when you’re speaking to them,” he said. “Those little social interactions are obviously important, but they have to be taught, as strange as that sounds.”

The school also focuses on providing students with opportunities to gain employment experience. One of the challenges in the blindness community is that greater than 70 percent of individuals who are blind or have low vision are unemployed or underemployed, Durst said.

“I think the main reason for that is a lack of education on the part of employers not realizing that those who are blind or have low vision have the ability and desire to provide good work for employers,” he said. “I think we have made some inroads with some of our programs.”

Dalrymple emphasized the role technology plays in the ability for those who are blind to thrive. He said that as a student, he would have peers read to him and do research for him, forcing to him to be dependent on others. Now, technology does the work. “(Technology) is fundamental because there is now no one standing between the person and the information. They are the ones filtering the information.”

Dalrymple emphasized the role technology plays in the ability for those who are blind to thrive. He said that as a student, he would have peers read to him and do research for him, forcing to him to be dependent on others. Now, technology does the work. “(Technology) is fundamental because there is now no one standing between the person and the information. They are the ones filtering the information.”

Durst said they encourage students to participate in extracurricular activities, saying that blind students can do the same things anyone else can do, with the right tools. “Given the right accommodations, our students can pretty much do anything a sighted person can do,” he said. “Advances in technology have leveled the playing field significantly for our students. We strongly encourage our kids to try new and unique opportunities, because unless they try it, they’ll never know if they can do it.”