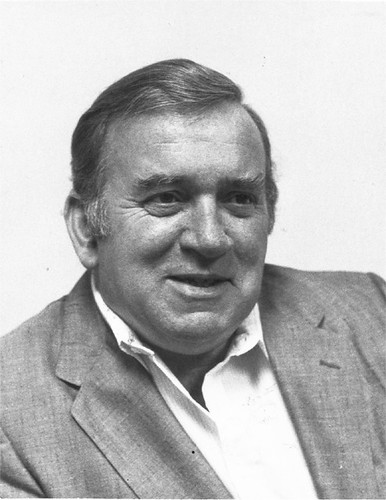

Writer / Dan Wakefield

I didn’t really get to know my own father until I was in my 40s. I was living in Venice, California, for a year starting my first novel when I came back to stay with my father while my mother was in the hospital after a serious heart attack in 1967. As a child, my father had seemed to me distant, reserved and often stern, polite but formal in a Southern gentlemanly kind of way. I was a little bit afraid of him. That week I spent with him while my mother was in the hospital, we got to know each other for the first time – having dinners and drinks at night, staying up late and telling stories. We laughed, talked and found out we enjoyed each other’s company – which I think came as a bit of a surprise to both of us.

He told me about a woman from Terre Haute who he had dated before he met my mother, and how this girlfriend sometimes drove down to see him in the coolest car of the era – a Stutz Bearcat! I wish now I had asked him more about his own childhood as the son of a stern Baptist minister in Shelbyville, Kentucky, and what it was like to be raised by relatives after both his parents had died by the time he was 13.

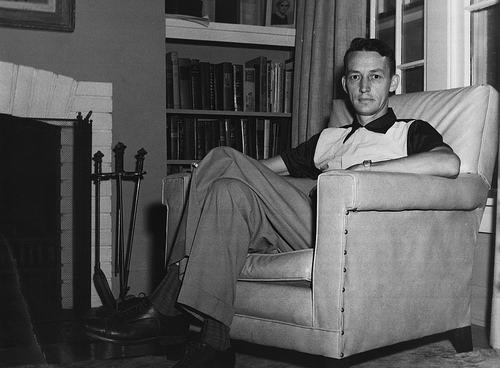

Not feeling comfortable with my father when I was growing up, I began to seek out and “adopt” fathers I admired and felt at ease with when I was a teenager, though I didn’t think of it that way at the time. My great good fortune was being named Shortidge High School’s sports correspondent for The Indianapolis News and The Star.

It was my duty (and pure pleasure) to write up or phone in the results of our football and basketball games and track meets, and as an extra bonus, I got to serve as assistant to the real sportswriters when they came to our home court or field for a big game. That meant I got to run up and down the sidelines of a football game with a clipboard and pencil, keeping track of statistics as I followed behind the professional reporter, or actually sitting at the scorer’s table at basketball games alongside the “real” sportswriter. I felt like “Somebody” – a person in his own right, just as if I were on the field or the court or the track. I too was a “player” but in my own way.

My first “boss” was one of my sportswriter heroes before I even met him – Corky Lamm, who not only covered games for The News, but also wrote columns for the paper that he illustrated with his own drawings. He was a talented artist as well as writer, and I’d followed his work ever since I was about 8 or 9. I devoured every day the sports pages of The News and Star. Before I had ever heard of Hemingway, Corky Lamm was my Hemingway. Unlike Hemingway, I could never imagine Corky with a hangover! He was sharp-minded, alert and quick – quick not only in his movements but also in his wit. He challenged my rookie opinions of sports and life and invited me to challenge him back.

My first “boss” was one of my sportswriter heroes before I even met him – Corky Lamm, who not only covered games for The News, but also wrote columns for the paper that he illustrated with his own drawings. He was a talented artist as well as writer, and I’d followed his work ever since I was about 8 or 9. I devoured every day the sports pages of The News and Star. Before I had ever heard of Hemingway, Corky Lamm was my Hemingway. Unlike Hemingway, I could never imagine Corky with a hangover! He was sharp-minded, alert and quick – quick not only in his movements but also in his wit. He challenged my rookie opinions of sports and life and invited me to challenge him back.

As well as his role as a mentor of my writing and helping me understand the games I was learning to write about, Corky was the first adult male to speak to me as if I were an adult. He never “talked down” to me, but told me what it was really like to be a newspaper sportswriter, explaining the downside as well as the rewards of his job (which came by way of personal satisfaction and pride in your work, not in the fatness of paychecks).

He spoke of his own frustrations with his job as well as its pleasures. He told me his boss was going off to cover big games whenever he felt like it instead of running the department. I was reading a book on sports writing, and I said, “I thought the job of the sports editor was to make the assignments, edit the copy and make sure the sports page was balanced and attractive rather than covering games.”

Corky was driving me downtown to the office when I said this, and he banged one of his fists on the steering wheel and said, “Out of the mouths of babes!”

I knew he was telling me I was right, that I had learned the duties of editors and reporters, and I understood the way a sports department was supposed to be run. I didn’t take it as an offense that he grouped me with “babes” or children since I knew it was a compliment – it meant that I knew what I was talking about even though I was just a kid.

I read his columns like a textbook, seeing how his prose was as sharp and exact as he was in person.

I gave Corky my own work to read – not only my accounts of games, but columns I wrote for The Shortridge Daily Echo, and he encouraged me, giving me compliments as well as criticism. It meant more than praise and encouragement from teachers – he was a pro! I was proud to introduce him to my parents, and they were happy to see that such a good man had taken me under his wing.

Even after I left to go to college in New York and after graduation when I wrote for little magazines my parents had never heard of, Corky assured them I was on the right path, that they didn’t have to worry and they could be proud of me and what I was doing. It meant a lot to them as well as to me, for they trusted Corky; they knew he was the best of men and that he only spoke the truth.

Through Corky’s help, I got a job one summer during college on The Star sports desk. It was great to be among those men with their ties loosened, their collars open, cigarettes hanging from their lips or mashed out in overflowing ashtrays as they pounded away on the old Royal or Smith-Corona typewriters, and the teletype clanked and rang with announcements of new stories that spewed out in long rolls of paper.

It was just like the newsrooms in the movies where Clark Gable was the intrepid reporter (except there were no long-legged “dames” since this was the sports desk in 1952 before the era when Lesley Visser broke the gender line of sports reporting for The Boston Globe – as well as mens’ hearts (for envy or love).

Visser would have been a fit companion for Gable in his era. (Historical digression: after moving on from The Globe to CBS, Lesley Visser became the first NFL TV analyst, covered every major sports event in America from the Final Four to the Kentucky Derby, and in 2015 was elected to The Sportswriters and Sportscasters Hall of Fame.)

Working on the sports desk of The Star that summer in college, I found my second “father.” In age, he was more like my “older brother,” but he knew so much more and was so much more accomplished than me, I thought of him as another “ideal fantasy father,” the kind you could hang around with, have a beer with and confess your hopes, dreams and frustrations.

He was Bob Collins, a short, stocky fireplug of a man who had starred as fullback for Cathedral High School. He later became the Sports Editor of the Star and wrote popular and sometimes controversial columns. He was the first local writer who understood the greatness of Oscar Robertson and the Crispus Attucks basketball team that became the first team from Indianapolis to win a state championship.

He was Bob Collins, a short, stocky fireplug of a man who had starred as fullback for Cathedral High School. He later became the Sports Editor of the Star and wrote popular and sometimes controversial columns. He was the first local writer who understood the greatness of Oscar Robertson and the Crispus Attucks basketball team that became the first team from Indianapolis to win a state championship.

It also become the first black high school team in America to win a state championship in 1955 – and added another one, for good measure, in 1956.

In that era of segregation, Collins’ praise of Attucks and appreciation of their artistry got under some white skins and brought Collins death threats, which fazed him not at all.

During that summer I worked on the Star sports desk, he gave me books to read – Budd Schulberg’s novel of Hollywood cut-throat wheeling and dealing, “What Makes Sammy Run?” and Kenneth Roberts’ great historical saga of the American revolution, “A Rabble in Arms” (the title came from a British general’s sneering description of Washington’s army as “a rabble in arms, flushed with success and ignorance”).

Collins spoke to me of books and literature, of sports and history – he was a one-man college education. We corresponded when I went back to Columbia, and one of my greatest thrills was when he visited me in Greenwich Village a few years after I graduated. I gave him a book to read – a new novel called “Rabbit, Run” by a young writer named John Updike. It was about a basketball player in a small town in Pennsylvania, and he admired it as I did. I felt in some small way I had made a token thanks for the books he had turned me onto, the worlds he had opened for me.

In my final week of my summer job at The Star, Collins assigned me to cover my biggest story yet – the championship game of The Industrial Baseball League. As best I remember, the game pitted The Allison Jets against The Link-Belt Warriors. I have no idea now who won. All memory of the game was wiped out when I handed in my story to Collins, and before even reading my copy, he wrote at the top of the page “By Dan Wakefield.” I felt I had just been knighted – I was a pro.

Comments 1